Images provided by interviewees with permission for use by UCLA Radio.

From Amsterdam to Tokyo to our home in Los Angeles, a global movement this Spring saw students occupy university grounds to express their solidarity with the people of Palestine. In the U.S., this movement followed in the footsteps of Columbia University, but encampments and occupations as a form of protest are nothing new on American campuses, whether as a part of the Civil Rights and anti-War sit-ins of the 1960s, the anti-apartheid movement in the 1980s, or solidarity with the Occupy movement in the 2010s. Protest is simply an essential foundation of democracy—freedom of speech and assembly—to ensure that people’s voices are heard. At the same time, as we found out on our campus here in Westwood, the web of repression facilitated by administration, government, and local officials in response to these protests also has a lengthy pedigree.

In the aftermath of the UCLA encampment’s brutal LAPD siege on May 2, I found myself reeling at the violence and system failures I had encountered, unable to focus on anything besides the media’s disastrous and misleading portrayal of the encampment’s last 48 hours. Distressingly, I found myself reading article after article that either shadowed or completely twisted the truth, often misrepresenting the encampment as a space of hate and restriction, when in reality, it was a community space highlighting a devastating and unavoidable global human rights issue, centered around popular education, community care, and mutual protection.

The stark contrast between media reports and my firsthand experiences, along with insights from other reporters, led me to wonder about other encampments both in the United States and internationally. What happened and what spaces were created? Were these spaces portrayed accurately in the media? How can independent student movements learn from and build off of each other?

Through phone interviews with organizers and encampment participants from the University of Amsterdam, Australia National University, University of Tokyo, and the University of Barcelona, I found the answers to some of these questions, and encountered surprising insights that in turn prompted numerous new questions. I saw patterns: in Amsterdam, as at UCLA, the rationale for police brutality often was the protection of buildings and property, instead of the protection of human life, much less an end to genocide in Gaza that we students are demanding. In Tokyo and Canberra, student movements struggled with how to deal with bad faith negotiations, and administrations that choose apathy and to ignore their encampments rather than have constructive dialogue. I learned about radical tactics taken by students halfway across the world, and shared a few of our own.

To be clear, these five universities by no means represent the totality of the encampment movement nor do I claim for them to, but through learning and comparing each of their encampments and the contexts they were built in, we can learn more about the student intifada and where it might be going next. Here’s what I took away from each talk.

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)

Total Enrollment: 44,947

Encampment Location: Royce Quad, Kerckhoff Patio, Dodd Hall

Start/End Dates: April 25, 2024 – May 2, 2024 (first encampment); May 23, 2024 (second); June 10, 2024 (third)

Status: Swept and removed by police, 200+ arrests

Demands:

- Divest all UC-wide and UCLA Foundation funds from companies and institutions that are complicit in the Israeli occupation, apartheid, and genocide of the Palestinian people.

- Provide full transparency to all UC-wide and UCLA Foundation assets including investments, donations, and grants

- End the targeted repression and policing of pro-Palestinian advocacy on campus, and sever all ties with the LAPD

- Call for an immediate and permanent ceasefire and an end to the occupation and genocide in Palestine

- Sever all UC-wide connections to Israeli universities, including study abroad programs, fellowships, seminars and research collaborations, and UCLA’s Nazarian Center.

UCLA was founded as a normal school in 1881 before becoming a University in 1919 and moving to its current location in Westwood. According to our own centennial website, 3000 students gathered in Royce Quad in 1934 to protest the university’s suspension of students for “communist” activities, launching a spirited tradition of protests over local, national and global issues that has been brought to life again by the Gaza humanitarian crisis.

My “interviews” at UCLA were the only ones that did not take place over the phone. Instead, they took place over days and weeks. They took place while browsing the books at the People’s Library, a folding table filled to the brim with books by Edward Said, Robin D.G. Kelley and others, centered around a honor system sign out sheet that was firmly adhered to. They took place as I sat on the hill outside Royce Hall on the night of May 1 after being hit by a launched piece of wood, when I met Misma, who was recovering from bear spray and offered me a ziploc bag full of vending machine ice to put on the bump forming on my head. They took place after the encampment fell, over delicious “By Any Beans Necessary Chili” prepared by the kitchen committee eaten at lectures at the People’s University for the Liberation of Palestine in Dickson Quad.

The first encampment at UCLA went up quietly in the morning of April 25, on Royce Quad, which sits between two of the four original buildings on our campus, Powell Library and Royce Hall. The encampment was set up with a list of demands, including calling for an immediate and permanent ceasefire in Gaza, disclosure of university financial assets, and divestment from companies and institutions complicit in the genocide of Palestinian people. The encampment grew slowly and steadily, featuring daily programming that included seder dinner during Passover, daily assemblies, study groups, art builds, movie screenings, and training on how to protest safely and effectively. It revolved around community care: featuring a med tent fully stocked by donations and manned by medical students and volunteer medical professionals, a food tent where volunteers signed up for shifts to prepare meals, and an art tent full of supplies to make posters. No money was exchanged for food, nor were insurance cards ever asked for: protecting and caring for each other was implicit. Students, faculty and staff participated, making the camp a rebuke to the notion of business as usual in the face of ongoing atrocities.

Since the inception of the encampment, groups of counter-protesters arrived nightly in attempts to weary those inside, by screaming, hurling threats, and even throwing a sack full of dead mice on the ground near the camp. On Sunday, April 28, three days after the encampment started, the administration gave a permit to a group of outside protesters to stage a counter-protest in the lawn next to the encampment, who brought with them a Jumbotron and several loudspeakers which were faced toward the encampment. After the scheduled counter-protest ended at 2pm, the Jumbotron stayed behind, where it remained until the afternoon of May 2, 2024, playing a constant stream of footage of the 7 October attacks, audio clips describing rape and sexual violence, annoyingly repetitive songs, and baby crying noises both during the school day as classes were in session, and throughout the night.

At 11pm on April 30, a large group of counter-protesters appeared, mainly men donning Halloween masks who seemed to have no affiliation with UCLA. They arrived at the encampment carrying chemical and physical weapons like bats and bear spray, which they aimed at unarmed students within the camp. Royce Quad looked more like a war zone than college campus, as dozens of students writhed on the ground, crying and holding onto their eyes, and calls for medics and saline became too numerous to count. This assault, which included metal pipes, pepper and bear spray, and fireworks, continued unabated for five hours, several of those hours while LAPD was present on campus before intervening. Two months later, only one counter-protester has been arrested, and his initial felony charge has since been dropped.

The following day, UCLA administration reversed their original stance and declared the encampment unlawful. Early in the morning hours of May 2, 2024, police officers from UCPD, CHP, LAPD, and other private security in riot gear took over campus buildings and strategic positions to mobilize a military response that included the use of flash bangs and rubber bullets ( directly fired at close range), culminating in 200 arrests.

Despite the brutality of its end, to many of us the encampment at UCLA was a beautiful space envisioning a better world, where community care and mutual protection were the foundations. It was a testament to the power of solidarity, demonstrating that even in the face of adversity, students could create a space of compassion, education, and resistance. At the same time, it reminded us and others that these very experiences were being obliterated in Palestine.

May 2, 2024, was far from the end of the student movement at UCLA. Since then, we have seen actions like second and third encampments, which were met with immediate police violence and arrests. We have also seen the establishment of the People’s University for the Liberation of Palestine, an outdoor daytime space that scheduled programming like teach-ins, discussions on the history and current situation in Gaza, and served as a sobering reminder that there are no universities left in Gaza. As we enter the summer, the student movement at UCLA will not waver. We remain steadfast in our commitment to stand in solidarity with the people of Gaza and will continue our efforts until Palestine is free.

Australia National University (ANU)

Total Enrollment: 18,934

Encampment Location: Kambri Lawn, University Avenue

Start/End Dates: April 29, 2024-May 27, 2024; May 27, 2024

Status: Ongoing

Demands:

- That the ANU cut ties with all weapons manufacturing companies, starting with BAE systems, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, and place a moratorium with any such ties in the future.

- That the ANU disclose and divest from all companies complicit in the genocide in Gaza, including all companies on the BDS list.

- That the ANU cut academic ties with Israel, including the exchange partnership with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem as well as any research partnerships with Israeli companies.

- That the ANU condemns and denounces the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the apartheid Israeli state, including the destruction of all universities in Gaza and the murder of Palestinian students and academics.

- That the Albanese Government immediately cut ties with Israel including, diplomatic, economic and military; stop allowing weapons exports to Israel; and recognise a Palestinian state.

ANU, like UCLA, is a public research university founded in 1946 in Canberra, New South Wales, the capital of Australia. It has been the scene of protests against the Vietnam War and apartheid in South Africa as well as students organizing for rights for First Peoples.

When the first tents of an encampment started to appear on Kambri Lawn–a central area at the ANU surrounded by restaurants, the student association office, the university pub, and residences–the administration initially seemed content to allow it, M, a third year Palestinian-Australian student at the ANU told me in our phone interview.

Unlike some of the other encampments, the ANU settlement does not have any leadership, and operates with a flat democratic structure that meets daily to decide on issues as a collective. Meetings take place daily at 5:30pm, with rotating chairs, and with volunteers taking minutes to keep the meetings somewhat on time (although I heard that they can still extend to 4-5 hours at their peak!). Dinner, which is supplied as a community meal each night, comes from outside members of the Canberra community, who bring it to the encampment.

The encampment movements in Australia were largely connected, with students in constant contact with their fellow students at the University of Sydney, and the University of Melbourne, trading insights on what they were doing and what was working. Unlike those of us in the Northern hemisphere, Australian university encampments faced a unique issue–the incoming winter, which at times led to frigid overnight temperatures, but never broke their resolve.

ANU administration invited ‘leadership’ of the encampment to meet mid May, but, as the encampment had no formal leadership, no encampment members attended this meeting. The following day, 7 students, seemingly selected at random and including someone who had never spent a night there, were directed to attend a meeting with administration under the threat of disciplinary action, where they were invited to divulge the names of other encampment participants, but did not acquiesce. Throughout these meetings, administration never was willing to enter discussion about the encampment’s demands, and refused to enter the encampment to negotiate.

Ten days later on May 27th, 2024, following many large rallies in support of the encampment, the ANU administration got security to pass flyers around at 8 AM declaring the encampment’s spot as a fire hazard, and called the police on the encampment to pressure encampment members to move. The ANU offered two alternate locations on the outskirts of campus, and threatened a move-on order (a move-on order is an Australian police order that orders you to go in a certain direction, and can be arrestable if not adhered to). To protect this space from the police, the community rallied around the encampment, and hundreds of students, community members, and staff came to support, and the police eventually left. Following a discussion in the camp, the encampment made the decision to move 50 meters down to a slightly less visible but still trafficked area.

The resilience and solidarity displayed at ANU’s encampment reflect the students’ unwavering commitment to justice for Palestine. Despite facing administrative pressure, relocation, and the harsh onset of winter, months after its inception the encampment remains a vibrant hub of activism and community that remains committed to forcing their university to meet their demands, and to continue fighting until Palestinian liberation is secured.

University of Amsterdam (UvA)

Total Enrollment: 42,324

Encampment Location: Roeterseiland Campus, Oudemanhuispoort

Start/End Dates: May 6, 2024 – May 6, 2024; May 7, 2024 – May 8, 2024; May 17, 2024; May 28, 2024-May 31, 2024; June 17, 2024; June 21, 2024

Location: Roeterseiland Campus, Oudemanhuispoort, Science Park

Status: Swept and removed by police, 125+ arrests

Demands:

- Disclose! Fully comply with the Freedom of Information case: disclose the university’s ties with Israeli institutions and companies, including educational institutions, as well as companies that profit from genocide, apartheid, and the exploitation of the Palestinian people and their land.

- Boycott! Cease all academic collaborations with Israeli institutions that participate in genocide, apartheid, and the exploitation of Palestinian people and their land.

- Divest! Cease all contracts with and divest from Israeli companies, and international companies/funds that profit from genocide, apartheid, and exploitation of the Palestinian people and their land.

The University of Amsterdam (Universiteit van Amsterdam/UvA) was founded in 1632. It is the largest university in the Netherlands and one of the largest public research universities in Europe. It also has a distinguished history of student protest from the global 1960s through issues.

Of all the people I spoke to outside of UCLA, the experience of Zeb, an undergraduate student at the University of Amsterdam, was the one that most closely mirrored the police repression encountered by students at UCLA. Zeb shared that the movement for Palestinian human rights at UvA had been active for over a year, with two student groups advocating for Palestinian rights for at least seven years. Despite these long-term efforts, they faced significant resistance from a historically pro-Israel university administration and a broader national context supportive of Israel.

Three weeks prior to the encampment, a small protest took place in one of UvA’s main halls, attracting about 100 participants. However, it was the encampment that started May 6 on the Roeterseiland campus that marked a significant escalation, as students set up outside the central building, the center for the majority of the departments at the University. Despite initial media interest framing them as dangerous, the group persisted, employing a flat democratic structure with no designated leaders, similar to that of ANU. The first few hours of the encampment were relatively peaceful, until Zionist counter protesters entered the encampment, causing chaos and providing the police and administration with a pretext for eviction.

Later that day, after failed negotiations between the mayor, administration, and encampment members, the police were called in, and the encampment was met with an intense, militarized response, which included riot cops, bulldozers, police dogs, and boats to enclose the encampment on the waterfront. Students continued to man the barricades, but the police violence continued to intensify, causing severe injuries to students including broken legs and fingers, and severe internal injuries. The police used extreme measures, including kettling and random beatings, resulting in severe injuries for many students, a level of brutality atypical of police in the Netherlands. Those arrested were subjected to inhumane conditions, including being trapped in transport buses for six to nine hours without access to basic necessities.

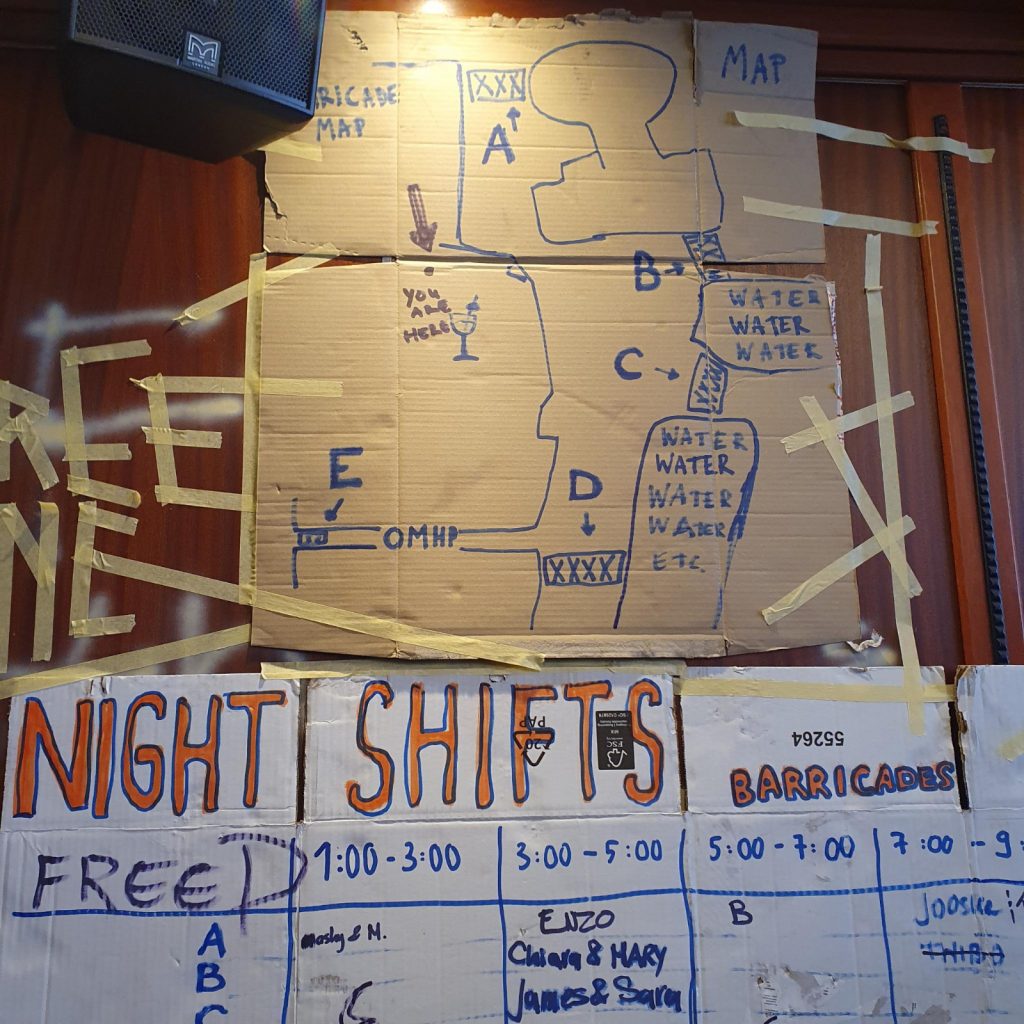

Despite these challenges, the students at UvA remained determined. The following day, large protests erupted in response to the police violence, and a group of marching students marched to an empty university building to occupy, Oudemanhuispoort. They established barricades made of paving bricks, bicycle racks, desks, planks and other objects to block paths to the building, and the encampment lasted throughout the night without interference from the police.

On May 8, riot police broke into the encampment in the afternoon, demolishing barricades with bulldozers. Protestors were cornered and removed by the police, and some bystanders were attacked without cause. This caused many demonstrators to move to Rokin, where they blocked Damrak, a main street in Amsterdam’s city center. The demonstration at Rokin continued for hours until police charged the crowds, resulting in dispersal and further clashes. By the end of the night, 36 people were arrested, with several injured protesters and police officers.

As we saw at UCLA, the repression and violence meant to scare protesters into complacency has been ineffective, and if anything, has radicalized protesters even further. Throughout May and June, protests and encampments have continued at the UvA campus and all throughout the city, rebuilding time and time again, making clear that the student movement in Amsterdam will stay persistent with their barricades, stay with their demands, and stay until their universities listen.

University of Tokyo (UTokyo)

Total Enrollment: 27,011

Encampment Location: Komaba Library Lawn

Start Date: April 27, 2024

Status: Ongoing

Demands:

- Declaration – Demand that University of Tokyo issue a statement calling for an immediate ceasefire and recognizing the ongoing Israeli military attack against Palestinians as genocide.

- Information Disclosure & Divestment – Disclose detailed information and partnerships regarding investments in and cooperation with companies and academic institutions that support Israeli genocide and apartheid in Palestine and are affiliated with Israeli and American weapons manufacturers, and sever ties with companies and academic institutions that are complicit in or related to genocide.

- Academic Boycott – Sever all inter-organizational relationships, including collaborative research and student programs, with Israeli universities and other academic institutions that are complicit in the ongoing genocide.

- Acceptance of Students and Researchers – Accept and support Palestinian students and researchers who face difficulties in continuing their studies amidst ongoing invasions, as well as those who face sanctions for protesting against Zionism in Israel and abroad.

- Guarantee of Student Autonomy, Freedom, and Safety – Ensure that no punitive measures or disadvantages are imposed on any student or participant who takes action in support of Palestine.

Tokyo University (Tōkyō daigaku or Todai) was founded as the first modern university in Japan in 1877 and has remained the nation’s top university. It also has a storied history of protest, particularly the daigaku funsō (university troubles) of 1968 and 1969, where global struggles linked with protests against the Vietnam war and the construction of Narita Airport.

Through a piecemeal web of connections, starting with a Canadian friend I met while studying abroad in Singapore, I made contact with Hana, a law student at UTokyo, who described themselves as a quasi-leader within the organization and were responsible for writing the letter of demands to the university.

The encampment at UTokyo began on April 27, 2024, and has continued to grow and solidify since then. Initially starting with one tent and a handful of members, the movement quickly expanded to include about 10 people within the first week. By May 6, they had submitted a formal letter of demands to the university with Nakba Day as the deadline (May 15). To apply pressure, the encampment organized a major protest on May 16, which saw about 400 people from 13 different universities participating.

The encampment is located on the large lawn in front of the university’s library on the Komaba campus, chosen because it is a central spot frequented by first and second-year students, who form the majority of UTokyo students that live on campus. Despite the university’s lack of response to their demands, the encampment has become a vibrant community, drawing support from students and faculty alike. Professors have donated tents and resources, and the encampment has relied heavily on donations from outside supporters, receiving everything from money to equipment.

Hana shared that their favorite part of the encampment is the strong sense of community and solidarity it has fostered. Despite its prestige, UTokyo has a large gender gap; 80% of undergraduates are male, and only 20% are female, and Hana revealed that the campus is not always a safe space for women and people of color. However, within the encampment the strict ground rules they implemented have ensured a safe and inclusive environment, free from racism, sexism, homophobia, and other forms of discrimination, creating a space where students can focus only on working together for Palestine without fear of prejudice.

The biggest challenge for the UTokyo encampment has been the university’s silence and the need to find effective ways to communicate and have the University discuss and meet demands. Internally, maintaining the encampment’s safety and learning to build and improve their community has been an ongoing effort, and organizers have relied on and reached out to students at universities like McGill University and Columbia University to gain insights on organizing and maintaining their encampment.

In Japan, the relationship between the US and Japan, rather than directly between Israel and Japan, plays a significant role in the nation’s attitude towards the student encampment movement. Beyond raising awareness, the Palestinian protests have also provided an opportunity for Japanese students to reconsider their country’s relationship with the US and its military ties with Israel.

University of Barcelona (UB)

Total Enrollment: 90,644

Encampment Location: UB Cloister

Start/End Date: May 6, 2024 – May 22, 2024

Status: Taken down by organizers after negotiations with University

Demands:

- Call for a ceasefire

- Recognition that the colonial occupation and apartheid practiced by the State of Israel are the structural causes of the conflict

- The split of all institutional or academic relations with Israel universities, research institutes, companies and other institutions

- Commitment to not carry out any act or omission that contributes to the Israeli occupation

- The creation of a commission of inquiry into possible institutional relations between the University and entities that do not comply with international humanitarian law

- Demand that the governments of Spain and Catalonia split relations with the State of Israel

Located in the center of the city, the University of Barcelona, founded in 1450, is no stranger to campus protests. It was a hotbed for action against the fascist Franco regime and also has become a forum for activism debate for Catalan nationalism and claims for autonomy in the 21st century. A year before they saw an encampment rise in support of Palestine, in April 2023 members of End Fossil Barcelona (EFB) slept in the garden of the University’s main building for a week, successfully getting their administration to listen to their demands, and eventually enact two-thirds of them.

The story of the UB’s encampment for Palestine starts in November 2023, when a group of professors and students from the University presented a motion to the senate of the University to recognize Palestine, genocide, and break with Israeli universities (an effort that was done in tandem with student groups at all the other public universities in Catalonia). This group included Adriana, a PhD student and encampment participant whom I spoke to in early June.

Initially at UB, there was no senate session scheduled until June, so the group forced an extraordinary session of the University Senate by collecting signatures of professors and students. Once the date was set for the 8th of May, organizers for Palestine at UB took note of the encampment movement across the world, and came up with the idea of staging an encampment to show solidarity with other student movements, and as a form of pressure on the academic senate as they were set to vote on the motion.

The encampment cropped up on May 6th in the UB cloister, outside the offices of many of the high powers of the University. As in other encampments, the UB encampment featured open assemblies to discuss the movement and its strategies, creating spaces where open deep debate took place. Additionally, the UB encampment received lots of support from Union members, many of whom came to physically camp with them, provide food and supplies, and support from afar in social media and webpages.

Hence, at UB protesters formed a successful double line of action–one that closely adhered to institutional channels (such as the presentation of the motion), and the other being the encampment–both of which worked strongly together. The motion was swiftly passed by the Academic Senate, which in turn sent it to the executive board, which had to vote again because the senates do not have executive power. Here, protesters encountered more resistance, and attempts by the board to water down many of the initial demands presented. After going back and forth for a week, all of the demands passed, and UB is now in the process of forming the commission to follow through on the work, making this the only call I had that resulted in concrete actions.

Hence, at UB protesters formed a successful double line of action–one that closely adhered to institutional channels (such as the presentation of the motion), and the other being the encampment–both of which worked strongly together. The motion was swiftly passed by the Academic Senate, which in turn sent it to the executive board, which had to vote again because the senates do not have executive power. Here, protesters encountered more resistance, and attempts by the board to water down many of the initial demands presented. After going back and forth for a week, all of the demands passed, and UB is now in the process of forming the commission to follow through on the work, making this the only call I had that resulted in concrete actions.

Why did the encampment at the UB find success when none of the other schools mentioned did? For one, Spain and Catalonia have a long history of protest. Additionally, after the end of the dictatorship in 1975, Spanish universities gained a great deal of independence from state powers, and it is uncommon for police to enter universities: over the past 30 years, police have only entered campuses twice. Additionally, Spain’s general public and government tend to lean more pro-Palestine than other European countries and the United States, which limited the external pressure on UB to crack down on the encampment and pro-Palestine student groups.

On May 28, 2024, Spain became one of three European countries to recognize the Palestinian state, along with Ireland and Norway.

A Blueprint for Solidarity and Change

The student encampments across universities worldwide have created powerful spaces of activism, community, resilience and solidarity with the people of Gaza. These encampments are more than mere protests; they are dynamic microcosms of collective action and solidarity, embodying the spirit of resistance against systemic injustice. By fostering environments of mutual support, open dialogue, and shared purpose, these spatial movements have shown how effective grassroots organization can be in challenging entrenched power structures and advocating for human rights.

The encampments have been particularly effective because they serve as visible, persistent reminders of the urgent need for action. They draw attention, galvanize support, and create a sustained presence that cannot be ignored by university administrations or the public. The strategic use of physical space—whether it’s in front of a library, an administration building, or a central campus lawn—amplifies the message and demands of the activists, forcing institutions to confront the issues head-on. Students have also galvanized the actions of faculty, staff and extra-university public supporters in a wider vision of community and action.

The widespread nature of these encampments and their resilience in the face of administrative and police actions – demonstrates that this movement is far from isolated. In a world increasingly divided by disinformation, militarized borders, police violence, and racial injustice, these student-led spaces and movements are beacons of hope. The encampments not only challenge the status quo but also offer a vision of a better, more just world. They are blueprints for the future, demonstrating how collective action and unwavering solidarity can bring about meaningful change.

Yet, as we celebrate these achievements, we must acknowledge that the suffering of everyday Palestinians has not abated. Changes do not happen overnight, and the road to justice is long and arduous. However, the perseverance and determination shown by students are essential steps toward real change. This advocacy forces people to pay attention, to reconsider their perspectives on Israel and Palestine, and to engage in a discourse that seeks an equitable resolution.

As these encampments continue to inspire and mobilize, they reaffirm the belief that a free Palestine means a free world. The liberation of Palestinians inherently entails the liberation of everyone, making this truly a people’s revolution. In the face of oppression, the power of student activism can indeed change minds, transform societies, and pave the way for a future where Palestine is free.