It has been a month and a half since protesters proudly waved the flags of Bangladesh and Palestine, side by side, over ex-Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s house. For the first time in weeks, student protesters were not met with state violence on the streets. Instead, they stood together, celebrating the end of a repressive government that had been toppled seemingly overnight by the youth of Bangladesh.

Bangladesh’s “Gen Z Revolution” was catalyzed by a series of student protests after the reinstatement of the government’s discriminatory quota system by the High Court. The quota system, which reserved 30% of civil service employment for descendants of those who fought for Bangladesh in its 1971 war of independence, was initially abolished in 2018 following mass protests.

Students at Dhaka University soon took to the streets against the quota system’s disproportionate support for members of Hasina’s Awami League party, blocking major intersections and occupying large swaths of their campus. As Hasina sent in police to violently quell the protests, killing at least 90 people in a single day, the Students Against Discrimination movement morphed into mass resistance against Hasina’s autocratic rule. But this revolution was not an instantaneous uprising— it had been developed and conditioned through fifteen years of government violence.

As students return to UCLA for fall quarter, we face unprecedented repression of free expression, from encampment bans to absurd limitations on political organizing. For our university to end its crackdown on dissent and finally divest from the genocide and occupation of Palestine, we must take notes from the students of Bangladesh. In this article, we offer three major lessons from Bangladesh’s revolution, coupled with concrete suggestions for students at UCLA, in the hope that we may forge new paths to divestment and liberation.

Lesson One — Change does not happen overnight.

Although Hasina was ousted after a remarkably short period of protest–only five weeks–this protest was situated within a long-developing tradition of Gen Z resistance. Civil disobedience under Awami League rule had become characterized by youth leadership, as they sought to decouple economic development from autocratic rule.

Hasina long used rapid economic progress, in large part driven by labor exploitation in Export Processing Zones, to legitimize her curtailing of democratic institutions and human rights. While the students of Bangladesh express great pride in their country’s flourishing economy, they questioned the neoliberal rationale that utilizes such development as justification for authoritarian regression. As Bangladesh’s youth faced skyrocketing unemployment (18 million young people alone) and an unraveling image of democracy, they rejected neoliberal paradigms in the hopes of a brighter future.

Networks of resistance started to expand in 2018, after the death of two teenagers due to a bus speeding out of control. In hopes of improved road safety, students occupied the streets for five days, even directing traffic in lieu of government presence. Similar scenes would emerge after the collapse of Hasina’s government, with citizens embracing lessons from 2018 as they directed cars through the streets— safety through community, not police repression.

These traditions would be further nurtured in the years leading up to victory. The abolition of the quota system (prior to its reinstatement this year) was forced by mass mobilizations immediately following the road safety movement. Gen Z flooded the streets again in 2019 after pro-government vigilantes murdered a student who had written posts on Facebook criticizing the Awami League. And just a couple of months before their revolution, less than a week after law enforcement tore down the tents on Royce Quad, universities across Bangladesh were the sites of mass protest in solidarity with the people of Gaza.

At each turn, the students of Bangladesh learned from their past mobilizations and continued to escalate their tactics: their successes and failures alike paved the way to liberation. As we face international calls for escalation, straight from Gaza and the West Bank, we must similarly build on our own traditions of resistance.

There are many movements we can look to in the past decade alone, from the Standing Rock #NoDAPL encampment to the Black Lives Matter uprisings of 2020. While the students of Bangladesh organized along generational lines–as elders often accepted antidemocratic rationalizations or migrated elsewhere–in the US, we benefit from cross-generational wisdom in resistance movements. It would be impossible to summarize this knowledge in a single article, so we will focus on one tactic of resistance that is too often overlooked.

Perhaps the most effective act of protest, spearheaded by abolitionist struggle in the US, is the practice of mutual aid: an exchange of resources rooted in community, not profit. The UCLA chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) has organized weekly mutual aid over the summer (Friday afternoons at the intersection of Westwood Blvd and Le Conte Ave), a powerful beacon of community. It bears repeating that, under a government solely concerned with strengthening capital and its militaristic interests, community-building is a radical act of resistance.

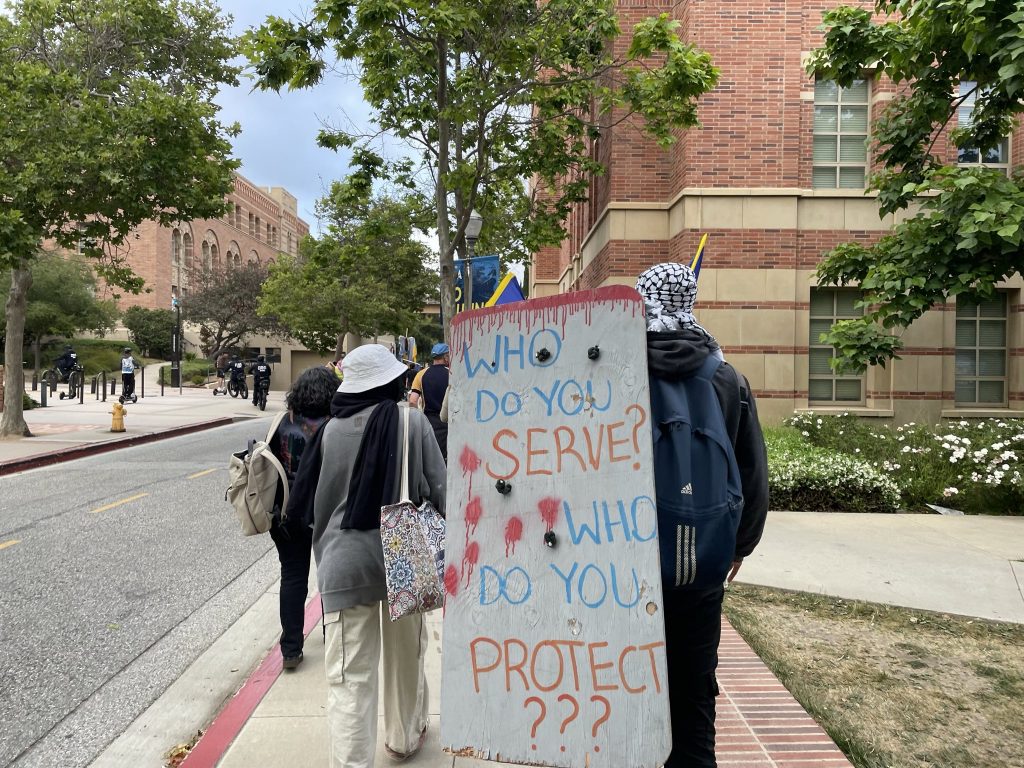

This community building is essential to refute the fallacy of university police: law enforcement does not exist to protect us. It exists to protect capital, and that includes the UC’s investments tied to the Israeli genocide of Palestinians. We keep us safe.

In order to undo the militarization of our campus and support the movement for Palestinian liberation, we urge members of and organizations within the UCLA community to support and expand mutual aid initiatives. Students often recount how effective the Palestine Solidarity Encampment was at delivering food access, water, and medical care to those who needed it; this was only made possible by mass community mobilization and support. To stand up to UCLA’s repression, we must nurture these community ties: we build our own resistance.

Lesson Two — We are far from alone.

Although Bangladeshi resistance was more closely delineated along generational lines, the students’ victory was still made possible by the support of the older generations. We cannot afford to minimize their contributions: just like Bangladesh’s students, we rely on our faculty, workers, and existing advocacy groups for victory.

Although Bangladeshi universities had become heavily politicized under Hasina’s rule, professors at Dhaka University organized to form the University Teacher’s Network (UTN) following government violence against protesters at the University of Rajshahi in 2014. As the organization grew to include academics both in Bangladesh and the diaspora, they played an instrumental role in the 2024 revolution.

On July 17, as Hasina escalated violence against student protesters, the UTN met in a hundreds-strong protest meeting. Facilitated by extensive coverage in both mainstream media and social media groups, professor solidarity inspired students to continue resisting in the face of heightened repression. Soon after, UTN members would free student leaders from detainment in Dhaka and stop the arrests of students in Rajshahi.

In Bangladesh, the UTN effectively countered attempts by Hasina’s government to make the student leaders feel isolated in their organizing, from labeling them pejoratively as razakars (a move that ultimately backfired) to cutting off the country’s internet. UCLA is playing by the same rulebook, as it deliberately seeks to divide its community by blaming anti-genocide protesters for police disruptions and embracing false narratives of anti-semitic exclusion at the original encampment. Contrary to administration’s assertions, the encampment (organized in part by Jewish Voice for Peace) observed and respected Jewish traditions, like in its student-led Passover Seder.

The UTN’s importance cannot be understated, and neither can the tireless efforts of organizations like Faculty for Justice in Palestine (FJP). From initiating the walk-out that brought hundreds to Royce Quad in support of the encampment to supporting teach-ins at the People’s University for a Liberated Palestine program, FJP has consistently amplified our calls for divestment. We must recognize and return the support of FJP, as well as other organizations like UAW 4811, in order to build a community capable of resisting UCLA’s discursive attacks as well as its physical ones.

Lesson Three — Solidarity is our strength.

Just as we seek to build solidarity across organizations and generations, it is crucial for students to continue building solidarity between movements against colonial injustice everywhere. Activists have become increasingly aware of the connections between systems of oppression that were previously seen as disparate, facilitating stronger movement-building and concrete steps toward mutual liberation.

This understanding is why, as protesters flooded the streets of Bangladesh, so did the Palestinian flag. Demonstrators told Somoy News that they carried the flag, a symbol of global resistance, because they “too are victims of discrimination and oppression.” Many of the students who occupied Dhaka University in protest of quota reinstatement had occupied those same grounds two months earlier, in an act of solidarity with encampments across US universities.

The practice of mutual solidarity, or mutuality, is powerful when not misused. As Mahdi Sabbagh writes in Renewing Solidarity (readable in the Palestine Festival of Literature’s anthology Their Borders, Our World), there is a “particular danger of diluting, of muddling, of confusing, that happens when we attempt to equate conditions across disparate timelines, disparate geographies, and disparate configurations of racial and colonial formations.” But “mutuality is a tactic that first requires and then further enables communities to listen and learn from one another to form ideological ties, coalitions, and triangulations of knowledge exchange. Mutuality is power.”

Therefore, as we seek to embrace traditions of mutuality, we must balance two critical tasks: learning from liberation movements across the globe (as we seek to do in this article) and always listening to the voices on the ground in Palestine. And, after estimated hundreds of thousands murdered in Gaza and the largest Israeli incursion into the West Bank since 2002, the people of Palestine are unequivocally calling for us to escalate our tactics.

There are various ways to build knowledge according to mutuality. We encourage members of the community to explore these different paths and find one that particularly resonates with them. Political education groups are a good starting point: a (non-exhaustive) list at UCLA includes SJP/FJP-organized teach-ins, the Student Labor Advocacy Project (SLAP) book club, and events organized by UAW 4811 Rank & File. For avid readers, we recommend the aforementioned Their Borders, Our World (edited by Mahdi Sabbagh), as well as Haymarket Books’s easily accessible “Free Books for a Free Palestine.”

In Bangladesh, the people rallied around Palestine as a symbol of mutual oppression, but also mutual hope. The road to liberation is a difficult one, but Bangladesh’s students show us that it is far from impossible.

We will not stop, we will not rest.

With UCLA doubling down on restrictions to free expression and campus militarization–clearly targeted against pro-Palestinian voices–it is clear that the violent responses to student protest that we witnessed last quarter will only escalate. This violence, perpetrated by the police but enabled by UCLA, is all too familiar.

It is reflected in years of police repression of student-led protests against the Vietnam War and South African apartheid in the US. It is reflected in the crackdowns against Bangladeshi students when they organized against an unjust quota system. It is reflected in Israel’s violence against student organizers and political prisoners in the West Bank and Gaza.

We have learned from Bangladesh’s students who flooded the streets, even when they were targeted, attacked and imprisoned. But we must also learn from, as the youth of Bangladesh did, the practice of steadfast perseverance in Palestine (صمود, or sumud), situated at the center of global struggle against violence and injustice.

Like the students of Bangladesh, like the people of Palestine, we must remain steadfast as we struggle against militarization, occupation and genocide. The students of Bangladesh did not win their liberation easily— they persevered in spite of draconian crackdowns and violent oppression. If we follow their lead, maybe then will the Palestinian flag be flown over UCLA as freely as it had been over Sheikh Hasina’s house. Maybe then will Palestine be free.

The views expressed in this article represent the majority opinion of the UCLA Radio Editorial Board. Editorials do not necessarily represent UCLA Radio as a whole.