INDIGO DE SOUZA @ THE FONDA [12/05/23]

Photos by Chloe Gonzales

I’ve been thinking a lot about destruction. Sometimes, in that self-concerned, navel-gazing sense, but often, literally, like that dilapidated church that used to exist on the corner of Strathmore and Gayley my sophomore year.

When they tore down the church last year, I was a little sad to see the end of a site my friend once deemed “the grit of Westwood.” I’m very much tied to places, and as a sophomore, I’d often leave my dorm at night to sit outside that crumbling building and do nothing. I was 19, and there was nothing to destroy there; I had barely formed the opinions, found the interests, or met the people that influenced who I am today.

But then you talk to people and you do things. You make mistakes. You find friends that you laugh and cry with so much. You might meet someone and wonder what it really means to capital-L-Love another. Sometimes you discover a song that fires your neurons until they’re fizzing like champagne bubbles.

And one day you look back on your days and realize that they aren’t so dull anymore. The people and the music and the mistakes have colored in the blanks, painting a picture that’s bursting in technicolor, so vibrant that you almost have to look away. You have so much more to live for and so much more that can be destroyed.

This natural progression of living is the heart of Indigo De Souza’s music. “I think that aging is a huge inspiration for my writing. When we are young, we do a lot of things for the first time. Everything feels fast and big and wild,” she said in a 2018 interview.

The Asheville indie rock artist’s songs navigate these turbulent waters of young adulthood, paddling through the complexity of relationships and questioning of identity and purpose, all with a candor that’s as blunt as it is humorous. With De Souza, the ride is ever-changing: whether it’s a celebration of her found queer community á la “Hold U,” or an anxiety-driven, fun-as-hell romp like “Take Off Your Pants,” you’ll relate, dance, and cry to her songs.

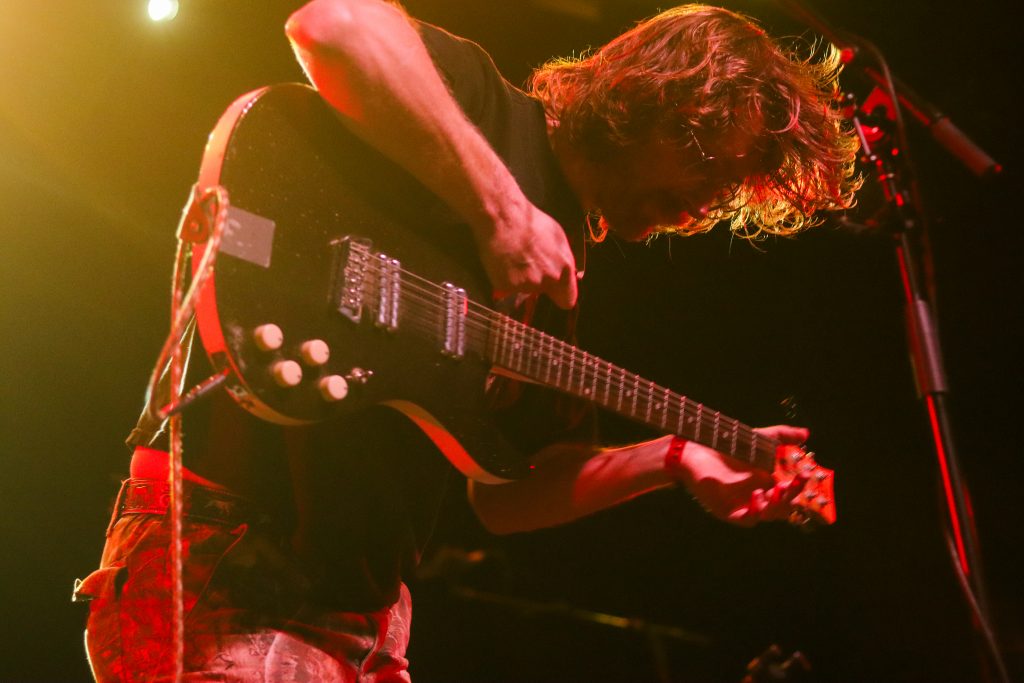

Tonight at the Fonda, we’re here to do all of the aforementioned bits at De Souza’s show. We all settle in as New York-based band Babehoven takes the stage. Their songs exist in a dream-state, drenched in a thick shoegaze haze that seemingly stops time. My favorite was their performance of “Fugazi,” in which the warm guitar strums and gentle drumming are reminiscent of collapsing into a loved one’s arms at the end of a long day.

“An idea, you leave me breathless,” lead singer Maya Bon confesses, shifting to a higher register at the end. Her voice heads home like a blackbird in resolute flight above our heads. She pauses to thank the crowd, as well as share how the band’s parents are in the crowd tonight. We can’t help but applaud – it’s a sweet display of community, and all of the audience can feel the love present.

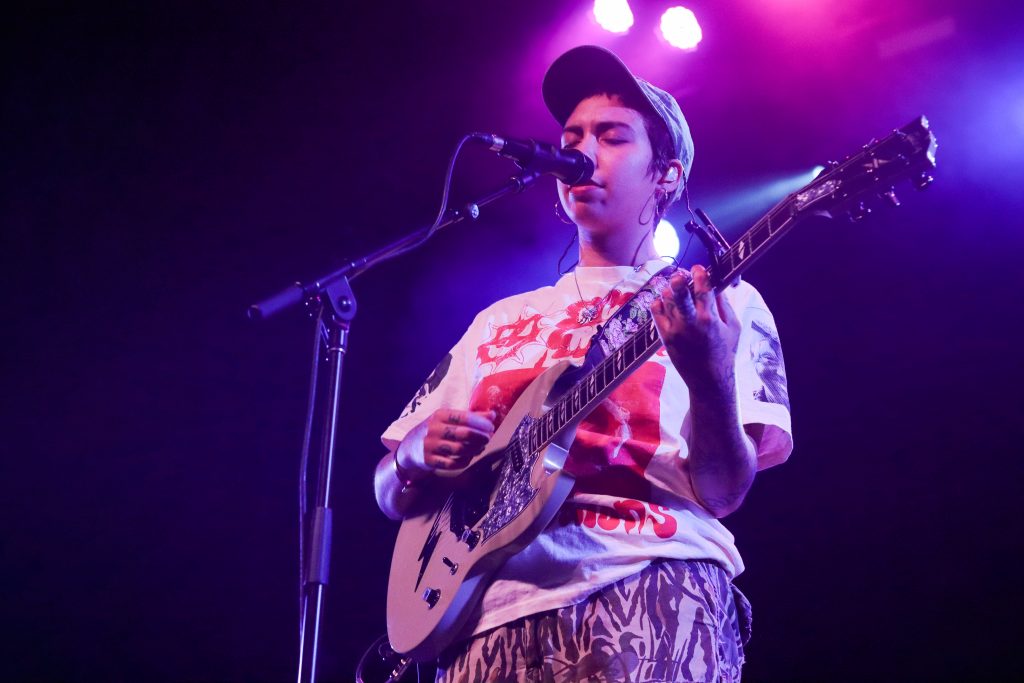

After a break, the Fonda curtains rise once more and De Souza, with her band, greets us with otherworldly instrumentals, as a lap steel guitar ebbs its way through the ether. De Souza’s eyes are closed as she tentatively steps towards the mic. Unsteady, yet gentle, bass synths reverberate around her. “Be my love,” she sings, repeating the words like a mantra, stretching them thin until sighing out the final iteration. The crowd is silent, enchanted by her vocal spell.

As she sings, she sways her hand throughout the air like she’s testing the waters before jumping into the river. “I was so nervous tonight,” she confesses. “Some nights it’s worse. But when I speak it, it’s like letting it all out.”

De Souza announces that they’ll be playing mostly unreleased songs, and we cheer in response. As a fan, it feels special for her to trust us with her songs before they’re released in recorded fruition. So we cling on tight to every lyric and chord of the performance, attempting to feel these songs for the first time.

De Souza’s music refuses to settle in a sonic niche, like in “Wasting Your Time,” where grimy guitar thuds give way to shimmering synths in a melodic chorus, only to return to an even grittier, angrier final verse. Instead, the dynamicity of her sound takes on shapes. When I close my eyes and listen to the band play, I see a sunburst-spiral, constantly growing and shrinking. It’s drenched in vibrant shades of tie-dye, the reds and the purples and the pinks and the blues bleeding into one another until you can’t pin down where one color begins and the other ends. Her music is messy and carefree and liberating, its dye staining my fingertips for days to come.

Many of these songs focus on change, and how painful, but necessary the act is. “You look at me like I’m an old picture you forgot to throw out,” she reveals, allowing herself to grieve a fading relationship. In another song, she confesses, “What am I doing here anyways, when my spirit is not?” De Souza’s music captures these difficult emotions – insecurity, heartbreak, outgrowing spaces – and wraps them up with us in a soft blanket, holding us tight as we try to make sense of them all.

Notably, De Souza is making music and touring with a new band, reflecting her themes of movement and renewal in real time. Listening to the group flourish onstage, it’s a testimony to having faith in new beginnings and trusting your decisions.

De Souza has never been bogged down by the sterile environment of a recording studio – just listen to how her voice traverses states of matter, going from a solid statement to an airy pleading as she repeats “I wanna be a light” in “Way Out.”

But it’s here when performing to a live audience, where she soars. De Souza is a skilled vocalist, controlling her voice as she explores a spectrum of emotion. She wails and she whimpers and she rages and she breaks. She is saccharinely sarcastic at times and quietly vulnerable at others. Behind her technical prowess, however, is a drive of the heart. She lets the music take her back to the feelings that shaped it, be it a dragging devastation or a high jubilance. De Souza’s willingness to feel is the keystone to her artistry, locking in all other elements to build the sonic structures that we, the audience, live in.

During “How I Get Myself Killed,” De Souza dampens her vocals in one breath and ignites it in the next as she sings about the rush of new experiences accompanying a coming-of-age. She feeds off the audience’s energy as we shout every question with her:

“Did you say anything on the night of my first hit? On the night of my first kiss? On the night of my first runaway?”

De Souza’s uninhibited delivery cuts straight to the gut, ripping out those searing memories and reanimating them like a voodoo practitioner. Singing along with her, I feel like I’m 19 again, like everything is new and exciting. Like I understand nothing about the world, but know everything. Like a heartbreak could shatter my whole being. Like a kiss could piece it back together.

As the band plays throughout the evening, there is always an underlying mortality tying together each song, a sense of inevitable destruction in the lyricism and production. The End is nigh in De Souza’s artistry; all her album covers feature skeletal figures (drawn by her mom), with her first EP, I Love My Mom, inspired by her realization that one day her mom would die. And her latest album’s title? All of This Will End.

I’m fascinated by De Souza’s fascination with The End. I think of death as a definitive destruction, and as we grow older, we undergo a multitude of demolitions. We love people just to lose them. We spend years cultivating identities and building communities, only to outgrow them. Our bodies fall apart.

So how do we go about our days, navigating our relationships and dreams and anxieties, knowing it’s all going to end anyways?

Instead of searching for futile answers, De Souza seeks to understand the present moment. “Once you actually understand that people are mortal and everything is fleeting and temporary, then you’re able to appreciate things more and kind of see people in a more compassionate way,” she explains in a 2021 interview with Flood.

In this view, it’s the brevity of our time here that makes the act of doing and caring so vital to our existence. I used to think of love as a persistence against the inevitable, but I’m starting to think that we love freely, not in spite of the end, but because of it.

And that brings us to the final song of the night. “I’m Not My Body” begins with gentle guitar strums and De Souza’s breathy vocals, until drums shock the song to life. Piano notes trickle down like autumn leaves in the wind and the lap steel guitar softly shivers throughout.

“I want to be, a redwood tree,” De Souza pleads amidst the clashing of the hi-hat. The redwood tree is known for being one of the oldest species alive, representing longevity, so it’s a distinct metaphor in an album about the end. In her desire to grow into something great, she adds depth to what it means to destroy. Perhaps the obliteration of some aspect of the self is necessary to grow the roots to something new, the way wildfires might leave behind a soil rich in nutrients.

She employs an operatic singing technique to finish the song, her spectral voice rising high above the crowd. The soft fog of the Fonda frames the stage and De Souza and her band appear larger than life as they close out the night. There is no encore; when De Souza says it’s the end, she means it.

We shuffle out of the theater and head back to our lives.

The next morning, I walk down Strathmore to campus, as I do every day.

I pass the church lot. My old haunt has become the construction site of a large apartment complex. Each day, I watch the building become a little more whole, beam by beam, pipe by pipe. Eventually, students will move in and live there. They might joke with their roommates on the L-shaped couch or drunkenly make out with someone on the balcony during a party. They might sob themselves to sleep in the bedroom or fall in love with how the morning light shades the bathroom. Maybe they’ll slow dance in the kitchen with someone while their soup simmers softly on the stove.

And someday, they’ll move out. Someday, the building will crumble and become dust once more.

But today, the building is still being formed. On the site, a large red construction crane sticks out, nearly 8 stories tall. When I walk past it, I pretend it is a redwood tree.