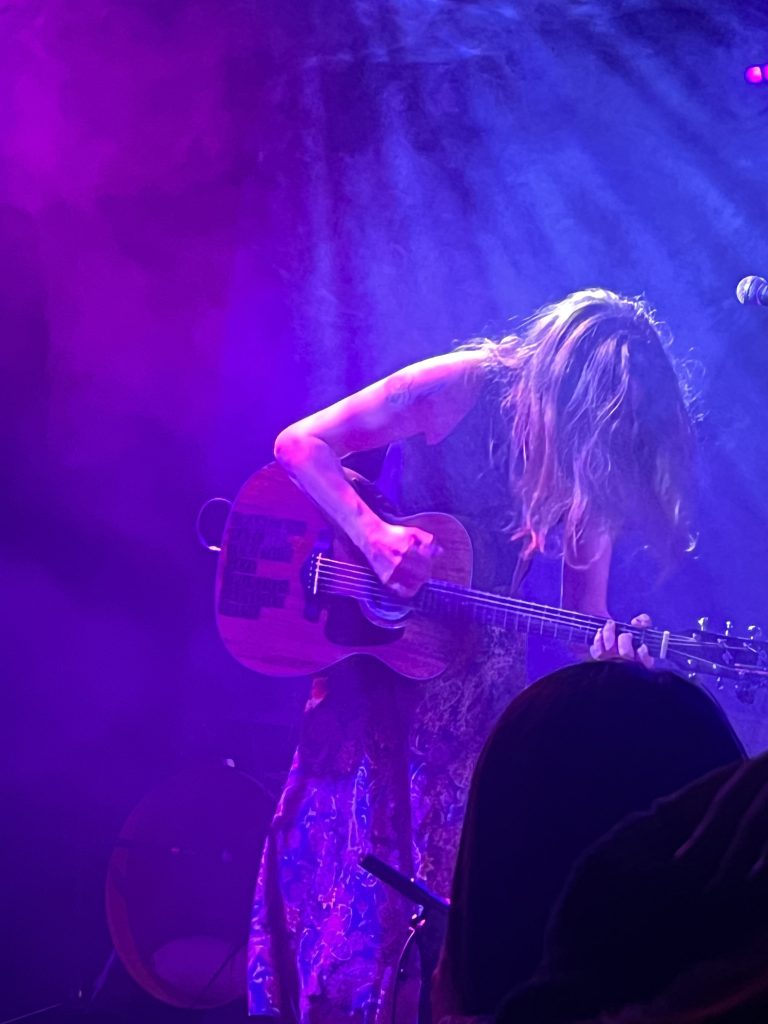

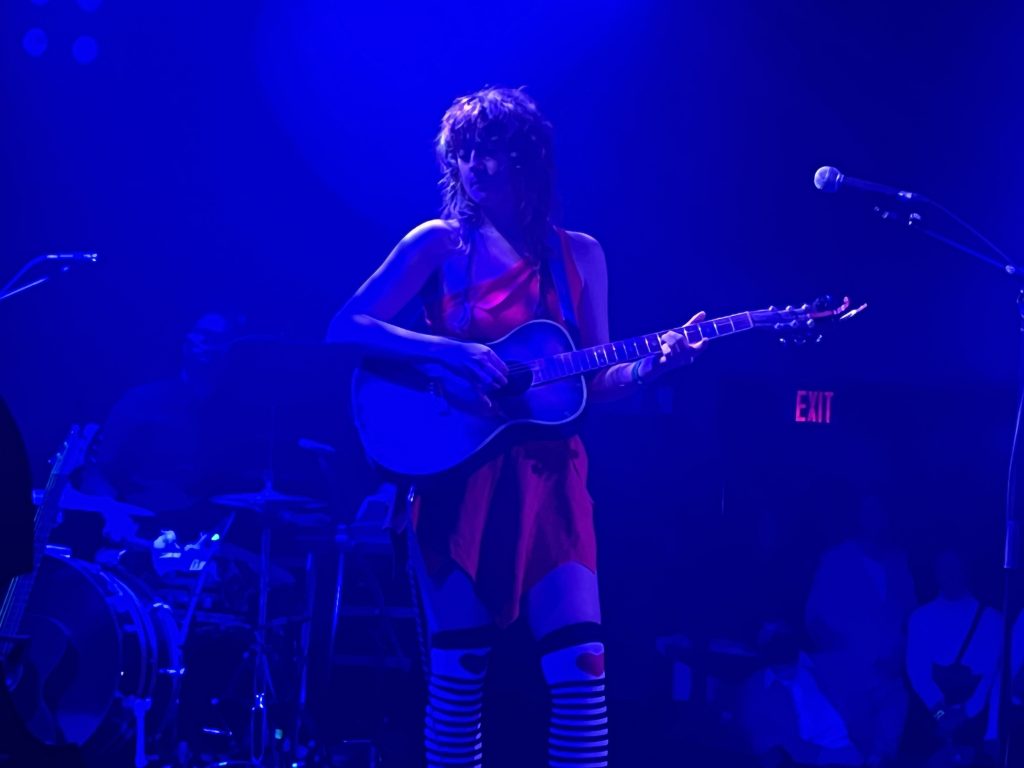

Photos by Sara Gorman and Gabriela Acosta

One of my favorite things to do after class is to attend live music. I was lucky to catch a show on Tuesday, January 9th, the second day of Winter quarter. I hadn’t planned to catch this show, but by miracle or perhaps just sheer coincidence, Sara shared the opportunity a few hours before doors opened. I had seen Odie Leigh on an Instagram reel, promoting her live performance in Los Angeles. Drawn in by her talkative songwriting style and rural appearance, I had considered it. And with that, we decided to give it a go. An excruciating class, outfit change, and uber ride later and we were there!

Amidst a crowd of queer teens packed to an extraordinary amount for a Tuesday night, the evening greeted us with an opening set from The Official Bard Of Baldwin County. If only one word could describe this performance, it would be raw. Reflecting on their life growing up in the Southeastern town of Spanish Fort, Alabama, notes of queer folk, punk, and old-time functioned as tools to tell the narrative of a strained relationship with parents, growing up queer, and the oppressive forces that left for an isolating world.

It was an interesting dynamic between The Bard and the audience. While singing and recalling rather niche experiences, opinions, values, and ideas, the audience seemed to resonate all the more, clap, and cheer along, expressing a sense of connection to one another through the musician’s shared individual story. This concert, in many ways, appeared to us as a physical manifestation of a digital community.

It posed the question of how digital communities are reshaping the folk music genre. While there are implications of the term folk music in the American music industry to describe Americana and country styles that fall outside of country-pop and country-rock styles (not to mention the racialized genre categories to distinguish White musicians from BIPOC musicians), the term folk music also can be read as localized musical traditions. We are interested in how American folk traditions shift as digital music-making communities rise and how this could be shifting our sense of locality.

The main act, Odie Leigh blew up on TikTok a couple years ago and has had a steady rise in popularity following her hit “Crop Circles.” Now performing her debut album for adoring audiences cross country, Leigh wears the title of “folk-misfit” proudly. Inspired by the classic folk, blues, and country music, so deeply sacred to the southern soundscrape from which she hails, and caught in the in between, in search of identity growing up only culturally-adjacent in an area of so much history, tradition, and faults, many found sanctuary in this self taught musician. Nostalgic, sentimental, melancholy melodies floated over an acoustic backbone of upright bass, acoustic guitar, and drums. Most people knew the songs by heart, and many filmed their experiences on their phones.

The room was packed and the audience was deeply engaged with her. We noticed a comfortable dialogue between the audience and Leigh. This prompted us to think about how musicians’ relationship’s to their audiences at large has changed with the rise of musician’s getting famous on TikTok. Leigh, like many other “bedroom musicians,” began taking over the music industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. The bedroom musician, someone who produces and creates their music with at-home technology (perhaps on a laptop rather than in a professional studio), has only become a more popular form of music-making during the 2020 shelter-in-place. And although the “bedroom” phenomenon predates the pandemic (for example, bedroom musician and UCLA-alumni Conan Grey got their start on Youtube), I would argue that it only further gained traction during shelter-in-place orders.

Social media platforms such as TikTok allow people the ability to engage with the same content regardless of their physical location. Similar to the effect created by blinding lights of a live stage, the musician cannot see the audience on the other side of the iPhone. Instead, they know there is a listener as view-counts rise. Audience members are isolated from each other physically but are on the “same side” of the musician/audience divide. Digital communities are then, not place-based communities. These communities express connectivity towards their collective experience by liking each other’s comments in the comments section of the video.

The performance begged the question of how TikTok is reshaping the intimacy of music-making and listening. How does the sense of intimacy that is performed by musicians in the personal vlog style of TikTok shape the way audiences engage with them in person? While there are no conclusive answers about the “good” or the “bad” aspects of this phenomenon, we encourage you to ask this question next time you attend a live music event.