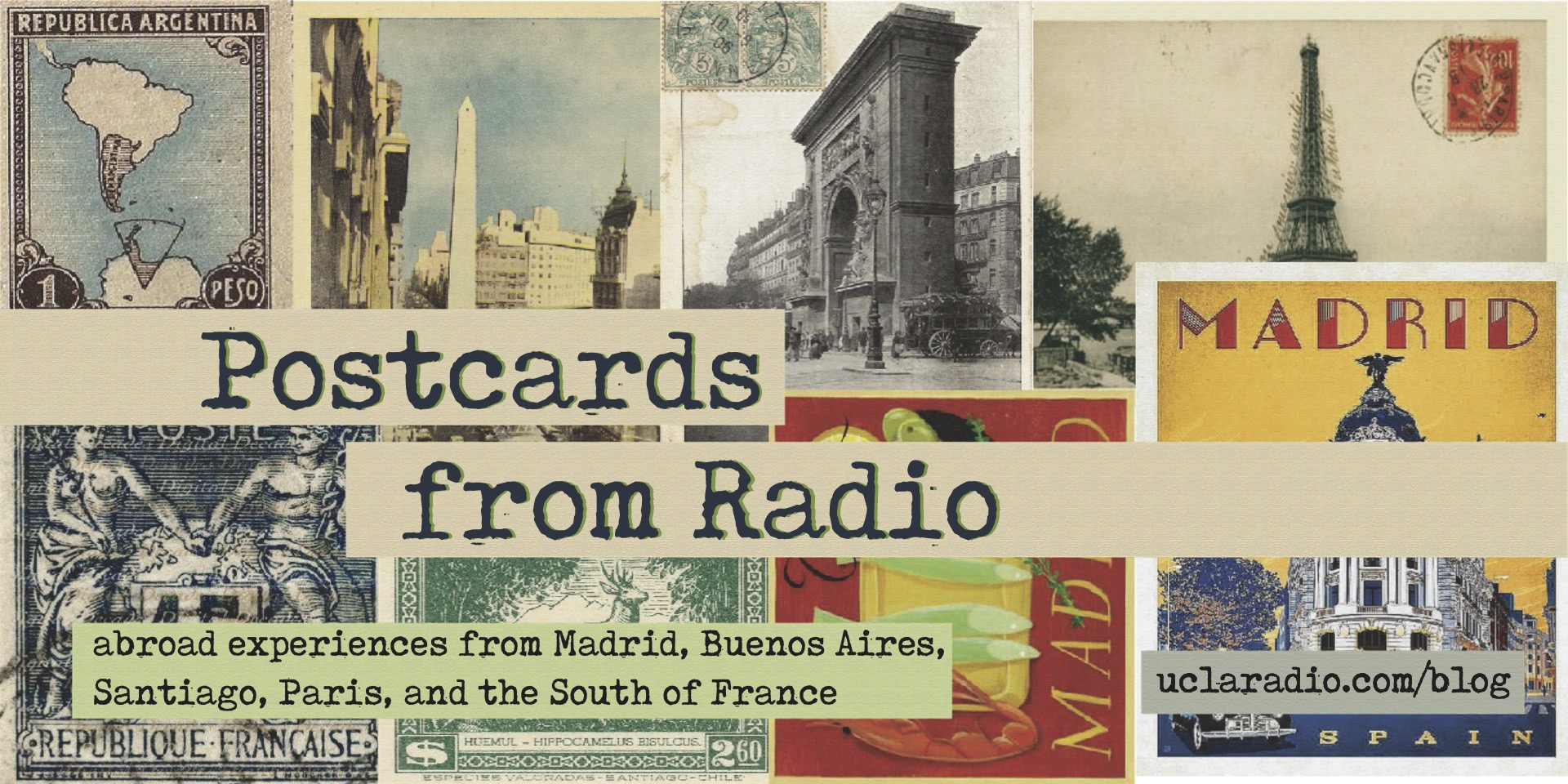

As the rainy Winter quarter comes to a close and dreaded finals fill up every library in sight, our Digi-Press members wanted to reflect back to a time before the chaos. And yes, if you haven’t guessed by the title, did you even know we studied abroad? From salsa dancing in Chile to buying pain au chocolats from the boulangerie in Paris — here are our postcards, with love, from Radio <3

~~~~~~~

Clementine Daniel – Buenos Aires, Argentina & Santiago, Chile

Anna Faubus – Aix en Provence, France

~~~~~~~

Madrid, Spain

Jeslyn Wang

If the excessive posting on Instagram wasn’t enough, you’re getting an article too. All jokes aside, it’s a lot harder to write this than I anticipated. Even after ten weeks of contemplating the last four months, I’m still not exactly sure where to start.

I remember the night before my 7am wake-up call to the LAX airport. Trapped between piles of painfully non-European clothes, I learned how hard it is to pack an entire semester of existence into one suitcase and one carry-on. My airport attire, a pair of sweatpants and a UCLA sweatshirt, was carefully chosen and neatly folded over my chair – a tradition I repeated before nearly every one of my firsts. My first day of school, my first piano recital, and now, my first time existing beyond the four walls of everything I had known.

I was told a lot of things about going abroad before I actually went. How it’s gonna be the “best experience of my life,” how I’m going to inevitably develop an affinity for cigarettes, and how everyone dresses so… European. Among a lot of other things, this was all true. But what did I know? The only certainty was what I was going to wear in the morning. And in that moment, it was enough.

There’s really only one thing in common with suburban Michigan, college dorms, and every other place I’ve called home at some point: none of it will remotely prepare you for living in a Madrid apartment, much less an apartment, for the first time. There, rather than proudly displaying street names on bulky green rectangles, each turn is adorned with painted ceramic tiles. On the corner of where I lived, Calle del Bonetillo was delicately brushed onto an ivory sign.

Our apartment building had an elevator on the first floor – the type that shouldn’t be running anymore, but somehow still does. Once you pass the slightly peeling walls and make it onto our medieval people-lifter, you’ll find our apartment on the fourth floor. I learned a lot of things while living there. The first being how much your neighbors will hate you when you stay out past 3am on the first night. Walls are thin, and being called stupid in rapid-fire Spanish is not fun.

Much more can be said about these four months, but I would be remiss to not mention our apartment’s red couch first. Like clockwork, I spent most mornings cramming my Spanish homework and sipping instant coffee on its maroon fabric. And at night, our couch became home to a concerning amount of Gossip Girl binges, wine spillages, and 2am shawarma runs immediately following whatever shit we’d gotten ourselves into. Regardless of the early morning hells that were forced upon us as a result of booking the cheapest RyanAir flights possible, or the late nights spent drunk off abroad freedom, the red couch was witness to it all.

There was an infinite list of restaurants, bars, and recommended sights that filled my notes app, but it would take an infinity of time to explore it all. Living five minutes away from Sol, the center of the city, I learned how inconsequential I was as I weaved past the endless tourist hordes, honking taxis, and promoters shouting FREE CHUPITOS every night without fail. Even the most routine of activities, from drying wet clothes on laundry lines to buying shockingly cheap produce and wine at the local Carrefour (sooo European, I know), there was a scary yet invigorating sense of newness that I could neither escape nor did I want to.

Out of the many abroad experiences I’m eternally grateful for, the monthly eight-euro metrocard might be at the very top. Whether squeezing between strangers during rush hour on Line 3 or speeding off Line 10 to make it to the maze-like terminals of the Madrid Barajas Airport, I discovered even more infinities than I could ever imagine. The Dali and Goya paintings that I’d first learn about in my art class, and then go see for the first time in the Prado and Reina Sofia museums. The sunsets at Temple de Debod, where there’d be guitar notes floating from street musicians and the guy that would write you poems for a dollar on his typewriter. The swan boats at Retiro, which were conveniently closed every time I tried to go, and the lazy days spent eating chocolate croissants on the park’s grass.

So much life in every inch of this place.

The endless flea markets and thirty euro leather jackets at the Sunday El Rastro. The espresso martinis and the cat-adorned walls of Chin Chin. The questionable promoters and one-euro shots at the painfully American clubs. The slightly overpriced empanadas and sangrias from the San Miguel Market. The never-ending stream of seven-floor Zara enthusiasts on the streets of Gran Via. The best pistachio lattes I’ve ever encountered from Naji. The vintage street in Malasana and the rainbow flags adorning the balconies in Chueca. And of course, the weekly dumpling runs from Chun-Li (thank god for its two-minute proximity to our apartment).

Oh, and autumn! How fleeting and beautiful were the changing colors of leaves, and how long it had been since I experienced a real fall. When Spain’s summer heat first dissipated into the orange and red, the rain no longer felt like a stranger. At night, I’d sit on my apartment’s balcony and stare at the dripping red glow from Cafe Madrid’s sign, watching the neon lettering paint the street I lived on. And as fall dissipated into Christmas markets and red-green street lights, we’d explore the cold with nothing but mulled wine and cheap scarves. Adjacent to Cafe Madrid was also a bookstore, covered in strangers’ sticky notes. In the four months I spent living across from their handwriting, I watched hundreds of passersby pause and tape themselves on the walls.

So many people in every inch of this place.

The lady at the bodega across the street, who’d ask if I needed a receipt every time I’d succumb to the temptation of Takis. The piano player at La Coquette, who rekindled my love for jazz. The barista at Faraday, who brought us homemade lemon cake and told us of his vinyls lining the coffee shop’s walls. And of course, the guy at the tobacco shop across from school, who’d rightfully laugh at my broken Spanish and shamefully ritualistic purchases. Clearly, two weeks of Duolingo combined with an addictive personality is a great recipe for cultural assimilation.

All the places I saw for the first time, and all the people whose paths I’ll never cross twice.

You see, I was told a lot of things about going abroad before I actually went. The same way I’m telling you now. And yes, it is indeed “life-changing” and it is indeed “amazing.” But above all, it’s a privilege.

And that is not to say that everything was rose-colored and perfect, because – in all honesty – it wasn’t. But, the ability to experience all this “newness,” to leave any four walls that we’re so accustomed to, is a rarity. And as fleeting as this was, that very transience is what it makes special in the first place. As much as finals season likes to induce a pain-staking nostalgia for what once was, I recognize now the futility in rooting ourselves in what has already passed.

Change is inevitable, and like in those four months, there’s nothing to do but embrace it. Studying abroad will merely be one of my many firsts, and as it dissipates into nothing but small-talk and fleeting conversations, I’ll let it join the other infinities of my life.

Paris, France

Ella Johnson

“You were abroad, right? Where were you, how was it? Did you love it? Does it suck to be back, how much do you miss it?”

For the first month back at UCLA, I encountered these questions on a daily basis. I loved catching up with people I missed, relating with friends who were also abroad about the mutual hiatus we had taken from our lives in Los Angeles. And it was easy. Most of the time people were already anticipating the answer I’d trained myself to give:“I was in Paris and it was truly a dream. I’m itching to go back and it’s been so weird being back in Westwood.” And of course the “Yes, I could totally see myself living there when I’m older… America is just… more miserable.”

I found myself detached from the experience as a whole, unable to talk about it with authenticity and regurgitating the same answers to those questions.

And yes, the trained answers do have truth to them. Paris feels like a time warp, where I was swept up into the arms of a city only to be ripped away just as I’d begun to touch my feet to the ground. It is weird being back in Westwood, and I do generally think Americans have a little less je ne sais quoi. But the regurgitated answer has grown old. When I began writing this, I’d been back for two months to the day. I want to share the details omitted from my practiced answers, knowing that it would not be a genuineaccount if I didn’t confess that although I did eventually make it to the Mona Lisa (two days before I flew home), I still have not stepped foot into the Musée D’Orsay (along with a million other things on my Paris to-do list).

I moved into my first real apartment in Paris. One of ten units in a converted nunnery, where our windows overlooked a primary school. The chatter of children began at 8am each morning – except for Wednesdays (did you know French public schools have Wednesday off??). It was around the corner from Rue Montorgeuil, one of the city’s famous ethnic food hubs. Each day I went to the Marché to buy fruit, frequented Le Chat Noir – a cafe where I met a lifelong friend – and ran along the cobblestone streets, weaving in and out of crowds that even Hollywood Blvd could not compete with.

In Paris, I was stuck in a weird in-between. My apartment of other UCLA students and my classes filled with other American students from my home state of California, were a cultural and linguistic haven. But I had wanted immersion! I wanted to feel overwhelmed and entranced. I wanted to fall into France and wake-up one day speaking fluent French. I quickly found that as soon as I stepped out of our front gate I was thrown into the throngs of the bustling city. Paris is no joke – it can sweep you away. After watching a boulangère point at my purple frilled socks stuffed inside my birkenstocks and whisper “les chaussettes!” to her colleague, I was glad to have one of my friends by my side to collectively laugh at the questionable choice. And shocked that despite the nature of the comment, I could at least understand what she had said! In French!

I became grateful to come home every day to the safety of what we made our home, even if that meant nights spent watching the Office or the speaker blasting Drake before a night out was hardly the immersive experience.

I do think the portrayals of going abroad place a lot of pressure on what the experience “should” be like, a series of experiences to check off a collective bucket list . Everyone’s stories of all-nighters at European techno clubs, the most beautiful beaches they’d ever seen, the layers of clothing they hid underneath to avoid paying the extra bag fee on the shitty airlines and the great food they had in Paris painted a picture I knew I couldn’t replicate.

I spent most of my experience abroad alone. Losing and simultaneously finding myself wandering the streets of Paris. I discovered that the promises of European techno clubs still couldn’t convince me to stay up past 12am if I had any say in the matter. I realized that there is really no point in the beauty of a beach if it is filled with hordes of sweaty people and requires a $40 taxi ride. That there is nothing to romanticize about lugging a carryon up metal steps to a Vueling airlines door. And if there’s one thing I could tell you I took away from my time abroad, it’s that the food in Paris isn’t any better than the food in Los Angeles…

That was my experience. There is not a one-size-fits-all experience studying abroad; being abroad, going on adventure; and I hope that we can collectively let go of this idea.Maybe we abandon the token abroad bucket list that includes Ibiza – although Calvin Harris was (maybe) worth it – and Munich Oktoberfest (but shockingly, I didn’t go and thus cannot comment on this one).

For anyone going abroad, I hope you are able to let go of any ideas of what it’s supposed to be like — because of what people have told you. You might love staying awake until the sun begins to rise and basking in the warmth of the ocean surrounded by chattering strangers. Or you might find, like I did, your favorite part of the day in the gray and misty 45 minute walk to school, the only time of tranquil in the city streets. Hopping on a flight after an all-nighter might not be your personal hell even though it has become one of mine – and that’s all okay. You might not experience any of those things. And that’s okay too.

To wrap up – here are some take-aways, my words of wisdom, for anyone who is going to study abroad. First, I’ll share what my best friend told me – don’t worry if you don’t make it to all the places on your list – you won’t; and it just gives you a reason to go back. Second – I’ll refute misinformed words from my father who told me the best glasses of wine come out of a tap (that may have been the case when he studied abroad in Paris in the 80’s, but it’s definitely not now). Updated pro-tip, the $6 glass is definitely worth it. Make sure you bring an extra empty bag, you will need it – and if I could fit all my clothes in one suitcase on the way there… then trust me, you can too. Don’t buy books; or do it with the intent of leaving them there. If you pass something you really want to do or see, a storefront that looks inviting – go in, do it, in that exact moment – even with the best intentions you will not make it back. If they have a menu in English, for your own sake, go eat somewhere else.

Lastly – I’ll invite you to approach it with one of the principles that served me well and is incredibly ironic considering the entire premise of this article. Try not to listen to music when you walk, and explore what it feels like to truly tune in. Resist the urge to put in your ear buds on the Metro. (Unless obviously you’re in the mood for a much-needed main character moment which is always valid – in that case, take a listen to “There She Goes” – the one by the La’s.) Do your best to be where you are, because it’ll be over much before you’re ready, and your “Abroad To-Do” checklist will sit in your notes app half-checked.

Buenos Aires, Argentina & Santiago, Chile

Clementine Daniel

My four months of living and studying abroad in South America were filled to the brim with new cultural experiences, from dance classes and live bands to backyard asados and beyond. As I sat down to reflect and write this piece, I put on my monthly Spotify playlist from August, when I had just arrived at my homestay in Buenos Aires. Mixed into a few songs that held onto my short-but-sweet California summer were the bachata songs I Shazamed in the Argentinian clubs and tracks from the Buenos Aires-based drumming group, La Bomba del Tiempo.

But before I go there, I’ll tell you about my first exposure to live music in Argentina, which was during our visit to a nearby Estancia. Estancia is the Argentinian word for a farm or ranch much like one you might have visited with your third grade class to pet goats, pick apples, and wander through the grassy fields. There, two older ranchers (called “Gauchos”) played us traditional music – one with a guitar and the other an accordion -as an expanse of green farmland freckled with goats and cows unraveled behind their wicker chairs. They explained to us how the country’s musical tradition was intertwined with its history and agricultural industry; not only had music been used as a form of protest and resistance during the six different periods of military occupation and dictatorship that Argentina experienced, but it was an art form that dated back to the days of European colonization and the displacement of indigenous gauchos from their homes and traditions.

Away from the Estancia and back in Buenos Aires, my friends and I discovered a bar that held a weekly live music show, and we proceeded to attend “Jam de la Grande” every Tuesday night until we left Argentina in October. It cost 3,500 Argentine pesos to enter the bar, Santos 4040, for the show, which came out to about $4 at the time I was there (today it would be only USD $2.92 because inflation rates have nearly doubled since my departure). La Grande played an incredible set each week, led by numerous different “conductors” that stood in front of the 8-person band and called out directions to play particular tempos, rhythms, and harmonies. Each song was seemingly constructed completely out of thin air, underlining the astonishing capacity of the musicians to watch their director and seamlessly improvise in front of an anticipatory audience.

La Grande was a subset of the larger percussion ensemble, “La Bomba del Tiempo,” which also performed weekly at a larger warehouse venue in Buenos Aires. Our program coordinators took my entire 49-person UCEAP group to their show one Monday night, and we all danced and applauded in amazement at the complex rhythms and thumping energy emanating out from the stage. After their performance, a handful of the drummers would make an appearance at the nearby Mondays nightclub, sneaking up below the DJ platform to shake the sweaty club floor with their booming drums and eclectic polyrhythms, offering a refreshing departure from the Bad Bunny and Rosalía on repeat each night (no disrespect). Our final weekend in the city, La Bomba played their once-a-month show that started at midnight and ran until 8 the next morning, playing consecutive sets on the warehouse stage and miraculously keeping us energized and enraptured until the Sunday morning sun began to rise above the nearby buildings.

Before we began the second half of our study abroad program in Chile, I headed to Rio de Janeiro with some of my friends to travel during our break. Our four days spent in Brazil were packed with delicious foods, magnificent views, and the kind of vibrant music that made you want to dance, sing, hug your friends, and be right up on stage with the musicians. As it had been recommended to us by multiple people, we headed to Pedra do Sal, a fair with live music, samba, and food held every Saturday through Monday in the Saúde neighborhood near central Rio. We drank caipirinhas out of plastic quart containers and sampled the empanadas and sticks of meat sizzling behind rows of food stands. We were grateful for the yellow and red-striped tent covering the street that protected us from the torrential rain pouring down that evening, though our sandals squished underneath our feet as we danced through the multiplying puddles surrounding us. We learned later that Pedra do Sal is actually a historic quilombo site, maintained and honored by the remaining descendants of the African community of fugitive slaves within Rio dating back to 1817. Keeping their communities’ history alive, the people of Pedra do Sal embraced and enraptured us with a fervent samba ensemble, as we spun and swayed to the music, packed in like sardines in front of the band.

My last stop on my musical tour of South America found me at Havana Salsa club on Friday nights in the lively Bellavista neighborhood of Santiago, Chile. Because the city of Santiago was much more sprawling than Buenos Aires had been, we found ourselves struggling to stumble upon lively bars and music venues as we had in the first half of our program. Havana Salsa, however, came recommended by nearly every Chilean we spoke to. Even my host dad in my homestay shared that he had spent his 40th birthday party at the salsa club, where they bring lucky birthday attendees up on stage to dance with one of the professionals. The salsa club featured a large stage surrounded by big group tables, where people could easily get up to dance or sit down for a pisco sour, Chile’s national drink. From our first night there, regulars at Havana Salsa invited me and my friends up to dance salsa or bachata with them; they paid no mind to our lack of skill and experience, and instead embraced us into the emotional and intimate partner dances, while also maintaining a level of respect and appropriateness that I found refreshing. On my final night in Santiago, I headed to Havana Salsa with a large group of my classmates from the program, with whom I’d shared so many songs and dances with over the previous four months. Having grown more comfortable with the dances, we spun each other in circles on the salsa club stage, singing and clapping until our hands hurt and our throats were dry.

Aix en Provence, France

Anna Faubus

The first day I arrived in Aix-en-Provence, a sunny town in the South of France, my host dad was pretty shocked to learn that I spoke only a couple of words in French. It was 11pm for me and the sun was blazing. He helped me trek my not-so-European amount of luggage up the hill from the train station to my new home. Although I was delirious and barely able to keep my eyes open, I was sure he did not sound very French. Francesco, as it turned out, was Italian, from Bari, and I would be living with the most wonderful French-Italian family for the next four months. With my internal clock screaming and my eyes heavy, we brunched.

As all adventures do, mine had high highs and low lows. But my biggest struggles turned out to also be my most rewarding feats. School was new, the language was new, and the people were new. Writing this piece is really the first time I’ve let myself feel the weight of my experience abroad because of the sheer effort it takes to put myself back in the shoes of Study Abroad Anna. I am still stunned by how much energy it took to absorb all of the daily newness – the exhaustion of a mind working overtime just to order a coffee. Reading through the detailed journal I kept, I am beyond grateful for the days that were so good that I didn’t want to write but forced myself to anyway. I documented the good days and the bad – because, make no mistake, there were both.

On the first day of my classes in Aix, one of my teachers walked us from the classroom to a cafe nearby. We ordered cappuccinos, and we chatted. We chatted! About learning a language, Malcolm Gladwell, dance, and the importance of putting yourself in uncomfortable situations. To say I was shocked is an understatement. I had never felt so heard in any of my classes at UCLA thus far, and it made me realize just how far a little effort to understand someone else will go. All of my classes there were like this. My teachers opened my eyes to what my education could be like, and I was determined to bring that back to LA. To not be so afraid of my teachers who lecture in front of 120 students, and instead see them as humans who have stories to tell. Aix–and my teachers and host family–taught me that my voice holds worth and that I should embrace my place in the world.

While I began to recognize the value in my voice, I struggled to express anything in French. I was humbled many times for terrible pronunciation, great pronunciation but terrible grammar, great grammar but not enough. My French did end up progressing, though, and by December, my journal was even scattered with Frenglish. Exhibit A: “Today I have encountered beaucoup de problèmes, et je ne sais pas what to do!?” My language breakthrough happened when my host mom, Fabienne, brought me along to one of her dance classes, and I was shocked to understand much more French than I did outside of the studio. I enrolled in more classes and couldn’t believe that I had never known that my 16 years of ballet training was actually teaching me French the whole time. Well, French words with strong Texan accents… but I could understand them! I understood four languages in those classes: English, French, Music, and Dance. It was the closest I felt to home in all four months.

If you’re thinking about studying abroad and have the means to do it, don’t let anything hold you back. My biggest pieces of advice are to go somewhere where you don’t know a soul, live with a host family, and, if you do, don’t turn down any offer to spend time with them. Abroad took me out of the American bubble for a second and reminded me of my privilege and the importance of using it to speak up for others. I wouldn’t trade those lessons or those people for anything.