This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity purposes

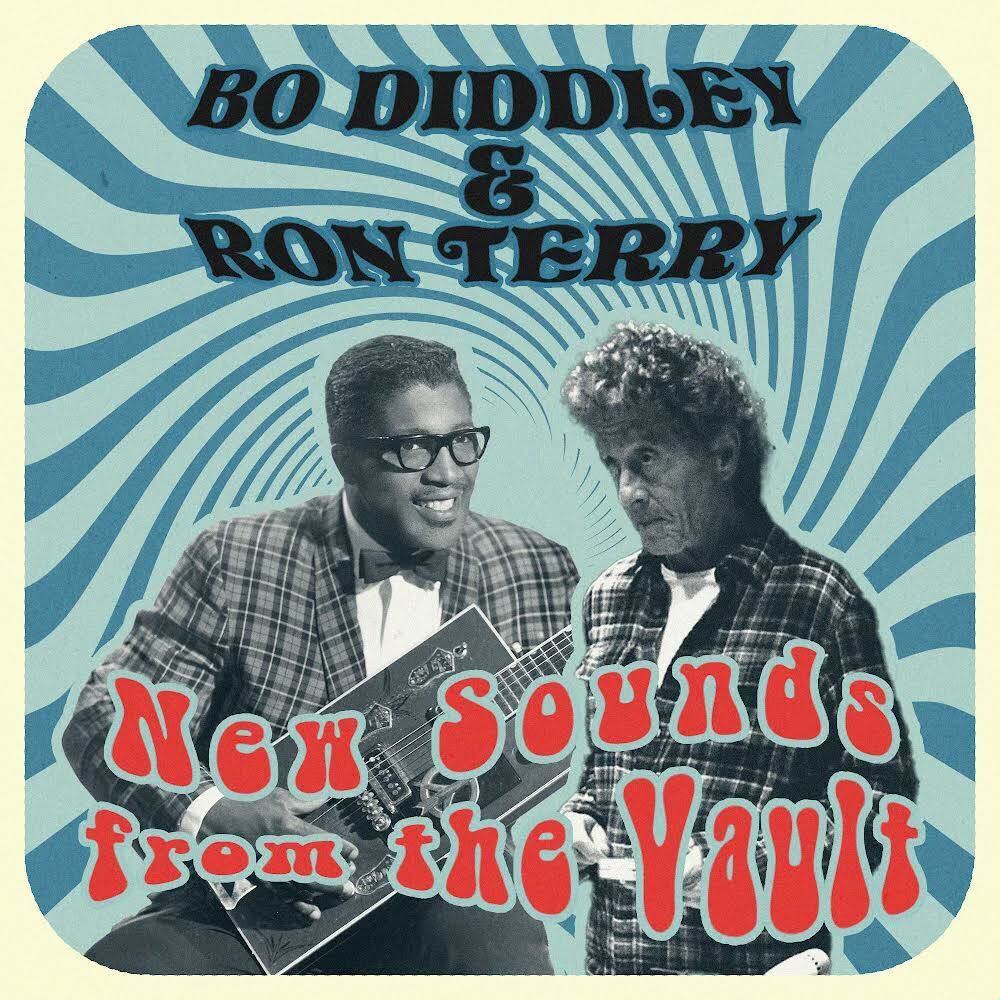

As I exit the bus around the corner from the iconic Village Studios, I worry I might seem out of place at an album release party. I enter the studio and await to be ushered into the party, and am greeted with warmth and kindness by Ron’s team at Vintage T Music. I walk past the plaques of iconic albums recorded here, including Fleetwood Mac, Lady Gaga, and Dr. Dre, and feel a sense of odd wonder mixed with a comfort I am surprised by. It feels like I made it home amongst music history, comforted by the memories I have with all the albums I have come to know so well, and imagining my favorite artists recording them. As I walk into the venue, with high ceilings, ornate Persian rugs, and mature leather couches, I am instructed on who is in attendance, and I am ravished by the feeling of friendship and creativity in the room. I make my rounds and begin to mingle and I feel validated in a way I never do at social gatherings, I attribute this to some kind of ancient creative magic that still lingers in the building, allowing it to envelope me from there on out. As I make my way to greet Mr. Terry, I am aware of another presence we are celebrating apart from Ron Terry, the man. Tonight, we are honoring Ron Terry’s legacy and his work with the late Bo Diddley. Legacies are entities of great importance in a town like Hollywood. A pretense that is separate from a star’s real personality, especially in the case of someone like Ron, who worked behind the scenes for headliners like Bo. As I learn more about him, I am surprised by his reach and his role in the foundation of so many iconic music industry moments. I separate Ron from his legacy because when I sit with Ron, he is a man of humility with genuine kindness in his eyes and pride for his work with Bo, which plays as the soundtrack of the night. Nevertheless, Ron Terry is a music industry veteran who has interacted with many of music’s most famous spirits. Mentions of Jimi Hendrix, Paul Simon, Bob Marley, and Chuck Berry throughout the night serve as a reminder of the time and place Ron has occupied in music and the legacy he has worked so hard to celebrate.

Ali: I’m so honored to be here. I wanted to ask some questions about the general state of the music industry right now.

Ron: I think it sucks.

Ali: Could you elaborate on how you feel about it?

Ron: It’s beyond anything. I mean, I make records. I still record in analog, and I worry about the sound. And everybody listens to their god-damned stuff on the phone now, nobody can hear shit. And I go, why? Why is that? How, how can you listen to music like that? But they do it. And I’m just an old guy, and I’m gonna do what I do. And they do what they do. But I think the industry in general, has turned into a Taylor Swift dance-athon. There’s nothing to do with music.

I mean, when you record digital, when you listen to shit on a phone, the sound doesn’t matter, it really doesn’t matter. I mean, people come over to my house, and they’re playing my album on a telephone, and I go, you got to turn that off. I can’t listen to it like that. I mean, I really can’t, you know, not just this album, any album, it’s just like that’s where it’s at.

Ali: Well, that leads me to my next question. I wanted to ask you what your favorite piece of musical equipment is at the studio, favorite on the engineering side, and also on the instrument side?

Ron: Well, I’m a guitar player. So I mean, you know, very prone to making sure the guitar is always perfect. But with me, the essence of a good song is getting the rhythm tracks down. If the tracks are good, then I start adding on guitars, piano, vocals. And as I said, I do everything in analog. My engineer passed away. But I had a really good engineer and I told him what I wanted. And then I go out in the room and make sure everybody does what I want them to do. Before I get to the studio, I rehearse for weeks, so when we get there, everybody knows their shit. I usually could get stuff in a couple of takes. I don’t I don’t need a whole lot of takes.

Ali: Do you have a most memorable moment just making this album or anything that you wanted to share about Bo Diddley?

Ron: In this particular album?

Ali: Yes.

Ron: Wow. These are tracks that I’ve had over 40 years with Bo. Some of them are tracks that I didn’t use on records. I never thought I was going to do anything with them. I write scripts for movies, too, and when the writers went on strike, everybody said, well go back and play with your fucking music. I went back and I put these albums together. Now some of these tracks come from a movie, which you’re gonna see in a few minutes, a movie I did with Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry. And then I took some of the tracks, and I, you know, mixed them and did an edited guitar here or edited a vocal there. And I put it on the album. It’s a lot of stuff over a lot of years. Bo, when he came to me, he said I need a white guy to produce my record, and I said, well, when you stop singing about yourself, I said, you and I can do some shit. And then I wrote a bunch of the songs, and he was cool with it. He really can sing, I mean, there’s no doubt about it the guy can sing. When he started doing all these other kinds of materials besides Hey, Bo Diddley, then all of a sudden we started making records and took off.

Ali: I hope this isn’t too personal. But what do you miss about him the most that he brought to the studio?

Ron: Bo was a sheriff, so he was a bit of a tight ass. It always took me a while to get him comfortable and relaxed, where we could actually just talk shit and not, you know, him being Bo Diddley, you know what I mean? But once we did that, then it was cool. It just took time, he had to trust me, I guess, I had to trust him.

Ali: Who do you hope this record reaches? Who do you want to listen to it?

Ron: People who care about music, people who understand what happened before and what’s happening now. I mean, there are some great players on this album, and I would like people to be able to respect them and understand that there are some great players. See, everything today is digital, you know, AI and all this shit. We actually played the shit. I mean, when I played guitar, I played guitar, I didn’t use AI at all, or whatever, either. But today’s world is very different. I want a little respect for the people who came before, that’s it. I’m not a preacher, but I want people to realize there is something that led to today. What we did yesterday has led to today.

Ali: What do you think is the most misunderstood aspect of being a music producer?

Ron: Nobody knows shit, the producer usually has more to do sometimes than the actual artist, because I’ve put down tracks, or whatever, and then brought in singers later. Then I sent everybody home, and I put it together and whatever else. The producer has so much to deal with the outcome. The movies are different. It’s the director who’s the guy, but in albums, the producer is the guy who knows what’s going on. Even the thing with Bo, I mean, I recorded this halfway around the world. And Bo was back home. I put certain things down with him. But then I went and did Billy Joel in Miami, and Ronnie Wood somewhere else. He didn’t know what I was doing, and then at the end, he heard the final product.

Ali: I wanted to ask you if you had any signature sounds throughout your discography and as a producer that you really gravitate towards. Is there anything that you kind of said kind of like a trick that you like to do or anything like that?

Ron: I don’t know if this will relate. But I started off singing in a choir when I was seven years old and got paid more money than my parents for making it. I am known for writing and producing great choruses. Big harmonic choruses. Whether it be a reggae record, whether it be with the Bo Diddley record. All my choruses. Usually a lot of black girls, I mean, that’s what I’m really into. I love the sound.

Ali: I wanted to kind of round it out and ask you a little bit more about your movie career and kind of what you’re up to there what your favorite moment was.

Ron: I started back in a club called the Town Hill in Brooklyn. It was a black club, and I backed up Jackie Wilson and Dinah Washington, and then I was the only white guy to play the Apollo, and I was backing up the Isley Brothers, and then Jimi Hendrix and I became very tight. I was very involved with Jimi Hendrix for a long time. Then I did Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, and then I got into reggae. I worked with a lot of big reggae things including Bob Marley and then I did an African record with a band called Zulu Spear. When Paul Simon did Graceland, he did it with the African harmonies in the back and all that which I thought were great. But he’s a white guy singing it, and I decided to go get African performers and do it authentically. Yeah, and Zulu Spear became the number-one album on the college charts in the 90s, early 1991. I enjoyed that record a lot. I’ve enjoyed reggae and African music more than I’ve enjoyed almost everything else.

Ali: It’s such an honor to talk to you. You know, I make music and I’ve been thinking a lot about how to honor the process of making music.

Ron: Yeah, that’s why I got to meet people that feel that way. And if you ever have questions, just reach out. As long as I’m alive. I’m gonna be alive for a while. Go enjoy yourself. There’s booze over there and food over there.

Ali: All right, thank you so much. Enjoy your night.