When Disney’s Aladdin premiered in 1992, its opening theme, “Arabian Nights”, sang softly of a “far away place” that is “barbaric – but hey it’s home.” In these lines, the American audience is removed from the comforts of their movie theaters or suburban homes and immersed into a foreign, rugged land characterized by savagery. For many children, this would be one of their first encounters with Orientalism – but far from their last. Edward Saïd, a Palestinian-American author, argues in his 1980 book Orientalism that Orientalism is not an explicit, deliberately-manufactured political project but an ideology that is all-encompassing in Western societies, internalized by all of us.

Orientalism can be defined as the Global North’s conception of ‘the East’, most specifically West Asia and Arab/Islamic people (though Orientalism can also be applied to other regions in Asia). Through Orientalism, the East can only best be reduced to the anti-thesis to everything that the Occidental world is. Stereotypes of the East as backwards, uncivilized, feminine are developed and transmitted through academia, the media, politics, art, and science. As a result of this exaggerated difference, Westerners are able to internalize supremacy and justify control, often under the guise of ‘aid,’ over the ‘submissive and untamed’ East.

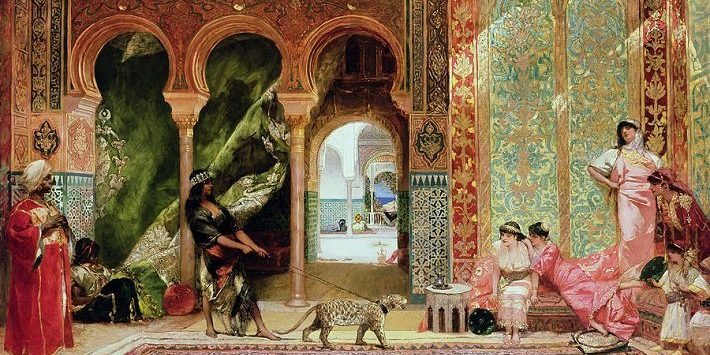

Early European conceptions of West Asia pushed a vision of exotic geographic and cultural splendor that was not necessarily grounded in reality. As Saïd writes “[i]t was the fame, attraction, and culture of the Orient that originally initiated the political, economic, and military interest in colonial domination […]”. By the 19th Century, European scholars dubbing themselves “Orientalists” had dedicated themselves to translating West Asian writings into English in the belief that it would progress colonization efforts, thereby ensuring the wealth of Europeans at the expense of West Asians.

But for all of Orientalism’s fantasies of Asia’s lush femininity, natural beauty, and exotic splendors, it ultimately requires a villain for Westerners to swoop in and defeat – and it finds it in the people of the lands they romanticize.

In 1970, Time Magazine published its September edition. The cover star was a faceless, nameless gunman representing the “Arab Guerrillas”. The lack of any identifying traits or human features given to this figure conveys that it doesn’t matter who is doing the shooting, just that the figure is Arab. This unidentifiable nature of this figure feeds hysteria within the global north about people of “the Orient.” Indistinguishable from one another, they are all threats that must be eliminated.

This trope can be seen in video games such as Cyberpunk 2077, which is set in a hyper-technological futuristic wonderland inspired by Americans’ impressions of Tokyo. Despite this, the game’s antagonist is a faceless Japanese corporation threatening to ‘take over’ and pervert society. Hollywood movies set in Baghdad such as The Thief (1940) introduce their villains with their faces obscured, identifiable only by their turbans and niqabs. American media continually profits from the aesthetics of Asian beauty while simultaneously stripping its people of their humanity and rendering them caricatures of “Easternness”. Ultimately, the villainization of Asian and Eastern culture is used to justify Western intervention, violence, and coups under the guise of “saving the day.”

Though classical Orientalism has its foundations in Europe, the horrors of the 9/11 attacks conceived a distinctly American strain of orientalism as a response, sometimes called “neo-Orientalism”, that has pervaded national identity. An Orientalist obsession with identifying the backwardness of the Near East governs American political discourse and fuels prolonged imperialist presence in the Middle East.

Following 9/11, many Americans searched for an answer to the attacks through exploration of “the culture of misogyny in the Middle East”, as opposed to probing into the political relationship between the United States and other nations, the unequal distribution of capital, or empire. This is not to state that violent crimes against women at the hands of extremist groups do not occur, but to acknowledge that American encounters with Arab nations often possess an astounding unwillingness to see SSWANA (South and South West Asians, North African) nations as states with political relationships and histories with the United States. Instead, the Global North favors treating conflicts as one-sided and borne from Eastern internal social ills.

Orientalism doesn’t only harm people in Asia. The faceless, nameless gunman of the Time cover is faceless – therefore he could be anyone, including your own countrymen. In the United States, racial and ethnic profiling continually singles out SSWANA Americans as potential threats to “American safety”. Asian Americans are burdened with the label of “perpetual foreigner,” merely temporary residents bringing in their backward culture and plotting against the United States. Orientalism is ever-present in white peers’ assumptions that their Asian friends’ families are ‘old-fashioned,’ ‘oppressive,’ and that they need to ‘catch up’ to reach modernity.

A critique of Orientalism cannot be equated with an affirmation that Eastern nations are true utopias that are merely misrepresented, nor is it to dismiss the very real differences between the United States and Asian countries and cultures. The goal is to reconcile how we can acknowledge the differences between the United States and Asia without falling upon predetermined patterns of prejudice and violence that sustain ongoing American imperialism.

Edward Saïd called for a shift in Western approach to dealing with the East, one that moves away from ‘viewing’ and toward communicating with Asian nations in a way that gives their people a voice to communicate their perspectives and lived experiences. This May, we can all stand to start doing a little less ‘viewing’ and a little more listening.