Genesis Owusu @ The Roxy [3/21/22]

Photos by Max Dallas

Standing by the Roxy’s stage, I was no more than twenty feet from the back wall and no more than thirty feet from the bar. Two tresses of muted red light dimly lit the entire venue. Minuscule but iconic nonetheless, the Roxy has long been a launchpad for fresh-faced future superstars, from Neil Young to The Temptations (both graced the stage in 1973, the year of its opening). Tonight, Genesis Owusu performs in the United States for the first time. Could this similarly be the start of something big?

My core had recapitulated the question I’ve been asking myself throughout the past year: do you believe in Genesis Owusu?

I do, I have to admit. I jumped at the opportunity to cover his tour. His 2021 debut album, Smiling With No Teeth, had been on my mind too long for me not to believe in him. My peers waited with me for the opener: a man in a JPEGMAFIA mask from his tour this winter, a teenager with a Revolver t-shirt, and a group of girls with matching, newly-purchased tour t-shirts. In short, I am in a puddle of Pitchfork readers. Inescapably, I am no different.

Is this what belief looks like? Certainly, ticket sales are testament to his growing popularity, but belief in an artist is more personal than ticket stubs and merch. Believing in an artist is allowing their work to ferment in the mind, cultivating its fullness of flavor through patience. It’s the conviction that a work’s beauty can be universally appreciated. It’s the backbone of an artist’s legacy, not their fame.

SHAYHAN, the opener, strolls onstage. Joining him are Agnes Azira on bass, Gideon Gable on guitar, and Nico Velasquez on drums. “Every band member has their own thing going on, but they came out tonight to support me,” Shayhan later explained to me while pulling up his bandmates’ instagrams. Each are small, LA-based artists looking for believers.

Shayhan has released eleven songs so far. Stripped back from their studio mix, they take on a natural, blues-rock-leaning air. He grimaces as he croons, his voice slightly raspy. He is barefoot. Between songs, the band jokes amongst each other and with the audience. Shayhan and Gideon’s hair undulate with the contours of their instrumental breaks, drawing the audience in with their swaying and bobbing.

The curtains close, and I chat with an ASU student who drove from his Tempe apartment to see Owusu. We had different favorite tracks, different memories and moments of growth etched into our experience of the album. He had bought a Smiling With No Teeth vinyl that he tucked under the front of the stage to protect it from getting crushed. He believes.

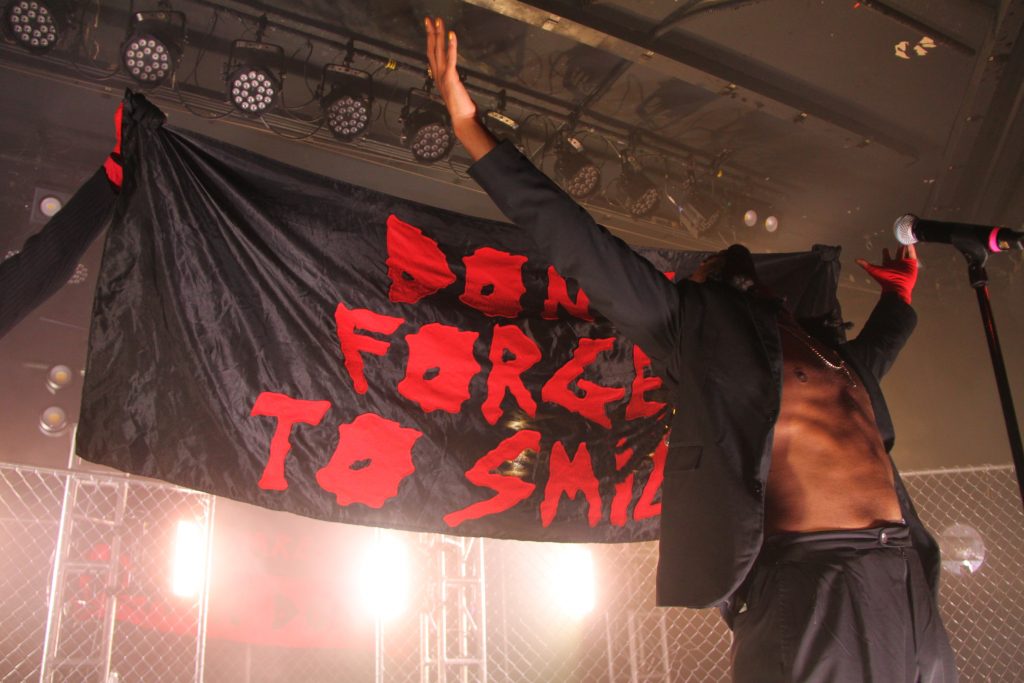

With a flash of the house lights, the curtains lift to unveil an unlit stage lined with chain-linked fences. Three men dressed as black dogs march onstage to heavy drumming. Owusu joins them, his head wrapped in bandages. He sports a gold grill, gold rings, and gold flecks in his dreads, just as he appears on his album’s cover. In a high-octane choreographed routine for “The Other Black Dog,” the dogs jump around, aggressively pulling Owusu away from the mic as he fights to sing.

While “black dogs” function as a colloquial metaphor for living with depression, Owusu’s rendering includes the pressures of racial discrimination. Kofi Owusu-Ansah and his family migrated from Koforidua, Ghana to Canberra, Australia when he was a young child. He and his older brother were the only Black students at their school. Ongoing were the challenges of finding identity in an environment that perceived them as other, challenges not removed from malicious manifestations of racism. In one instance away from school, a white Australian called Owusu a “black dog.”

“Here’s another black dog jam. It’s easy to get in, but hard to escape. I guess that’s why they call it a jam…”

Each track lingers, morphing into an unfamiliar groove before flowing into the next. Feeding the flow are Owusu’s spoken-word poetic interludes which artfully incorporate his lyrics. Notes of funk, jazz, old-school hip-hop, punk and even ‘80s rock season the performance. Owusu laid the foundation of Smiling With No Teeth with a five-piece band, crafting each track with bits and pieces from recorded jam sessions. Although Owusu’s Black Dog Band did not join him onstage, the backtrack was tight, displaying brief, previously unheard context from the album’s source recordings.

Last year, following the release of Smiling With No Teeth, Owusu sat in his bedroom for video interviews with various music journalists. Critically acclaimed vinyl sleeves line his walls, from Enter The Wu-Tang to A Love Supreme. In shaping the style of his music, it didn’t feel authentic “succumbing to one regionality,” as he put it.

Most notably, he shined on a seamless three song run of “Waitin’ On Ya,” “Void,” and album standout “Gold Chains.” Gleaming falsetto, snapped poses and coquettish twists elicited cheers, but his ecstasy veered into frigid sorrow as the groove changed. Submerged in blue lights, he tore the bandages off his head to bare his mind. Escapism, lamentation, and protest flash before us as he acts them out onstage. Smiling With No Teeth is an instinctive distillation of his upbringing, and his symbolic choreography helps maintain thematic cohesion across its diverse soundscape.

Sweat beads on his body and face as his lamentation turns swiftly into protest. With a militant urgency he fights his black dogs. He leads an anti-Nazi chant to the pulse of “Whip Cracker,” and rips the dogs’ masks off during “Don’t Need You.” Despite his hostile confrontations with the fractures in his spirit, Owusu’s message is ultimately one of love rather than fear. Each is a note to self, a needed look in the mirror. Pretending everything is ok is not an option.

Growing warmer and more candid as he ends his show, his exit from the stage prompts thunderous applause and chants for an encore. Owusu answers with “Black Dogs!,” a rattling neck-breaker, and one of the album’s deeper cuts. In truth, he didn’t have many songs to draw from – no surefire encore-like statements deep in the vault that he hadn’t already performed. This will do for now.

When Genesis Owusu returns to the United States, he will need a larger venue than the Roxy. A new album will enclose his inner thoughts, and so will a new wardrobe, new choreographed routines, new visual metaphors, and new sonic palates. Rather than attaining fame, his main goals are exploration, expression, and growth. Therefore, he has little to prove and much to share. For Owusu, this is the first chapter in a long book.