For the average museum-goer, looking at art is a passive experience – concerned mainly with the aesthetic presentation of what we see before us. However, taking a critical approach to the diversity of artists represented reveals the insidious and exclusionary practices that exist in many “respected” institutions, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In particular, art produced by women and people of color is consistently displayed at lower rates in mainstream museums. Art collectors and curators reveal their biases in the pieces they acquire, and the nature of visual art makes concealing unbalanced representation far easier by hiding an artist’s identity behind their work.

The Guerrilla Girls, who describe themselves as “anonymous artist activists who use disruptive headlines, outrageous visuals and killer statistics to expose gender and ethnic bias and corruption in art, film, politics and pop culture,” began in 1985 as a feminist group dedicated to addressing the lack of women’s representation in established art institutions. Known for their gorilla masks and pseudonyms that connect the movement to historical female artists like Frida Kahlo and Gertrude Stein, the organization remains active and currently has several pieces on display in the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum.

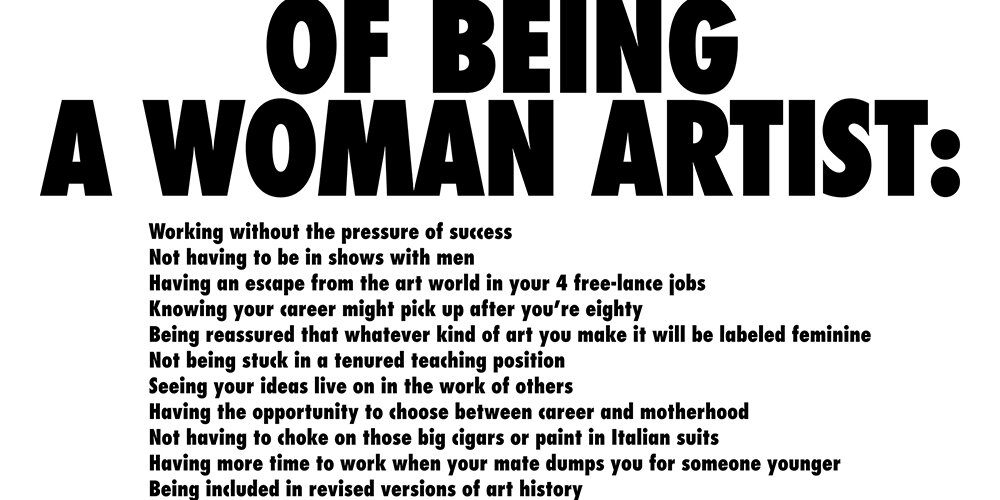

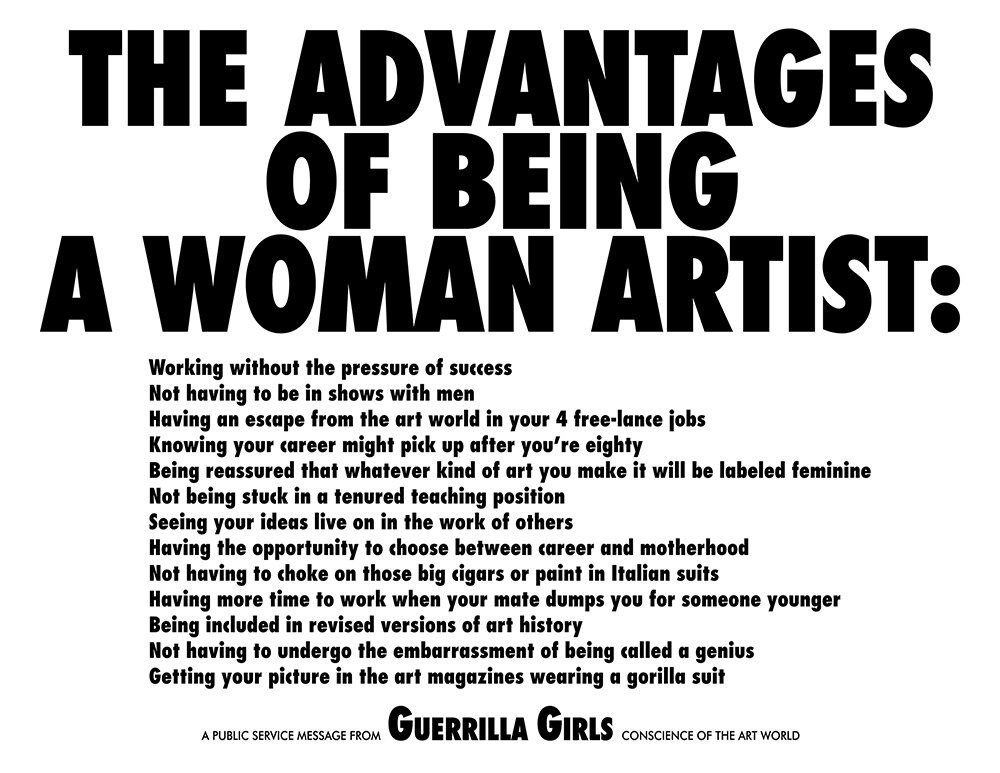

Visiting the “Put It This Way: (Re)visions of the Hirshhorn Collection” exhibition was my introduction to the organization’s work. Their text-forward design style stood out in the gallery and called my attention to various issues of discrimination that are not typically discussed in popular media. By clearly conveying a message without obstructing its meaning behind layers of subjective artistic elements, the Guerrilla Girls offer clear critiques of social issues with a consistent focus on combating social issues, particularly in terms of how they affect female artists. The irony present in many of their pieces, particularly “The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist (1988),” stuck with me as a uniquely comical way to expose major social injustice.

Since their early stages, the Guerilla Girls have used the strategy of directly naming culprits, whether they be individuals or institutions, along with concerning statistics regarding female representation to reveal the often overlooked truth about discrimination in the arts. For example, a 1985 piece was released to shame four widely-respected museums that failed to hold a proportional number of one-person exhibitions of women’s art. Further emphasizing their message, the Guerilla Girls released a recreation of this piece in 2015, which reveals worryingly slow progress while reinforcing the institutions’ failure to fix their mistakes after years of public outcry.

The Guerrilla Girls are indiscriminate in the organizations they critique, also addressing the treatment and representation of women in Hollywood and political causes relevant to traditionally underserved communities outside the arena of visual arts. Two pieces, “The Anatomically Correct Oscar (2002)” and “Unchain The Women Directors (2006),” focus on how the majority of Oscar nominees and winners for writing, directing, and acting have been white men. By expanding the sphere of their influence, the Guerrilla Girls not only advocate for a wider range of artists but also reveal the dark truth behind various institutions and encourage necessary corrections.

While the organization currently stands for intersectional feminism, critical responses to the Guerrilla Girls’ movement in its early stages pointed out its overwhelming whiteness. As an invitation-only organization founded by white women, the Guerrilla Girls faced issues of ethnic diversity for years. They continue to receive criticism for their use of gorilla masks, which bear racist associations that reveal white privilege in the movement’s origins. The connotation of the gorilla mask for many Black women is deeply personal and connected to the dehumanization faced by people of color.

In 2008, Black Guerrilla Girl Alma Thomas spoke to the Archives of American Art about the group’s symbolism, saying “I never wanted to wear the mask, but I always had to bow to the symbology that the Girls had locked into that was so powerful.” While the gorilla mask became a through-line for the movement’s ironic approach to exposing institutional discrimination in the arts, it failed to consider its other associations or the ways it would deter women of color from joining the movement.

In response to these criticisms, the movement pivoted to include advocacy for a wider range of individuals, with pieces like “When Racism & Sexism Are No Longer Fashionable, What Will Your Art Collection Be Worth? (1989)” focusing on both women and artists of color and “At Last! Museums Will No Longer Discriminate Against Women And Minority Artists (1988)” referring to the landmark Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1988 as it affects these demographics.

While problems certainly exist within the Guerrilla Girls and their racially-insensitive imagery, the statements made in their artwork hold true, and revealing the dark underside of major arts institutions continues to be important to dismantling these discriminatory practices. Exposing the intentionally homogenous reality behind seemingly varied artwork forces museum-goers and all purveyors of media to apply a more critical lens when exploring collections of art by considering who is compiling them and what biases might be reflected in their selection.