“The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.”

Italo Calvino, “Invisible Cities”

Driving down Olympic Blvd on the way to Weyes Blood’s show served quite literally as a trip down memory lane. Just a few years back, I’d take the exact same path to get to school every day. Now, I found myself treading old stomping grounds, preparing to do press coverage for my college’s radio station. When I first came across Weyes Blood’s music in high school, would I have expected to get this sort of opportunity? But more importantly, would I have even known that I’d make it this far?

Looking back, my uncertainty wasn’t unfounded. After all, an invisible disease had put the world on hold, innocent lives were being brutally taken at the hands of militant forces, and the nation had split into disparate halves. Even the sky looked like it could melt right onto the earth, its viscous flow confining our tattered world in amber, showcasing just how much we fell off.

It probably doesn’t help that I was also about to graduate high school at that point. I was supposed to start thinking about what I wanted to do with my life, but I couldn’t even tell if I had a future ahead of me. After all, when the world is so interested in engineering its own ending, how is that supposed to make you feel? As much as my high school teachers tried their best to quell my anxieties, my solipsism had taken hold of me and I felt doomed to a life of utter obsolescence, unable to do much about everything going wrong and set to continue living without intention. My existential dread had consumed me so deeply to the point I wrote a graduation speech so dark that my English teacher refused to let me present it to the unassuming crowd of stubbled boys and manicured girls.

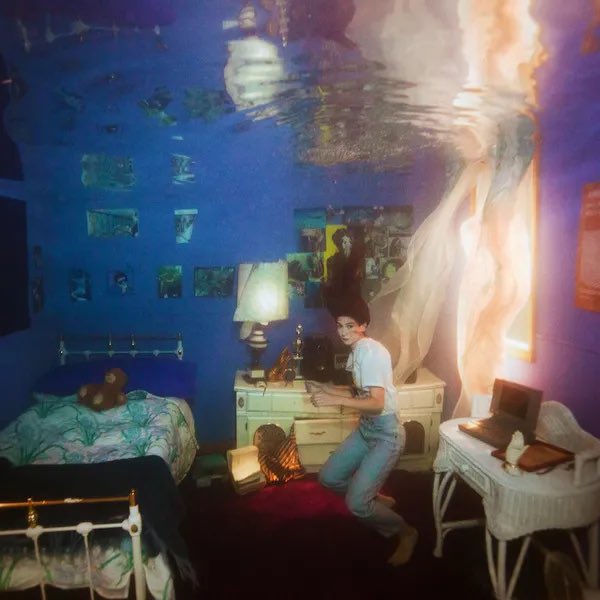

It’s no wonder Titanic Rising held such a tight grip on me. Even the album cover provided a moment of quiet calm I needed at the time. In it, Weyes Blood frontwoman Natalie Mering quietly stares at us from her underwater childhood bedroom, almost as if we caught her by surprise. Your eyes begin to gravitate towards the memorabilia scattered in the background, posters and furniture symbolically disheveled by the rising waters. But no matter how suffocating the bright blue water may be, you refuse to swim back up to the surface; you’ve finally sunken deep enough to tune into the songs of the sea.

Credit: Brett Stanley

“A Lot’s Gonna Change” opens the album with a bed of airy strings, floating like steam atop a river. Once they all vaporize into thin air, quiet piano chants give way to Mering’s opening verse. “If I could go back to a time before now / Before I ever fell down,” she imagines. If she were given the chance to impart a message onto her younger self, she has but one thing to tell her: “You’re gonna be just fine / But hey / A lot’s gonna change / In your lifetime / Try to leave it all behind / In your lifetime.” When “born in a century lost to memories” and “falling trees,” Mering speaks with the knowledge that her younger self will eventually grow into a world that is losing interest in grieving change. Back then, the world had her arms wrapped around her. Now, she realizes that climate change, false narratives, and dating apps will deeply trouble her.

Much like me, Mering was plagued by the same dilemmas. When it feels like the planet is no longer giving us a chance to live, is it even worth it to continue living and loving? With so much going wrong with the world, surely there’s gotta be someone up there trying to save us from the hand we’ve been dealt. Surely, life shouldn’t feel this strained, this difficult. But on the forlorn “Andromeda” and “Something to Believe,” Mering has difficulty finding proof of a cosmic helping hand. We’re left with no other choice except to look for answers among ourselves.

There’s a small problem though: seeking human connection has always been a notoriously sticky thing. “Everyday” and “Wild Time” are considerably more tapped into the current zeitgeist of the digital age and, because of it, understand the fragility and volatility of human relationships that much more. In “Everyday,” Mering laments about how modern romance has distorted into something entirely alien: “True love is making a comeback / For only half of us, the rest just feel bad / Doomed to wonder in the world’s first rodeo.” In an age where we judge potential partners based on the quality of their online dating profile or the thirst traps they AirDrop to us, Mering feels like we’ve made the pursuit towards meaningful human connection so needlessly complicated.

On “Wild Time,” Mering directly addresses our burning world and the collective climate anxiety that’s consumed us all. But while Mering does argue that we have a moral obligation to revolt against the institutions that enabled all these climate disasters, she also doesn’t judge anyone for eventually succumbing to the dread. “Don’t cry,” she sings. After all, “it’s a wild time to be alive.” Even if we should be actively working to change the world for the better, she understands that it takes time to get used to all these sweeping changes and that it can be pretty burdening and strange to be alive in a time like this. It’s a song that starts quietly but ends with such devastating earnesty that it honestly chokes me up every time.

I think songs like “Wild Time” in particular choke me up so much because, as I’ve transitioned into my adulthood, I’ve also begun to grasp the urgency and the emotional burden of this whole mess. I’m currently writing this from Washington State, where wildfires in Spokane have enveloped the city in ashen smoke and rendered the Pacific Northwest air unbreathable. Back home in LA, I get a call from my family telling me that a violent hurricane is passing through the city. I’m probably being dramatic but right now, it feels like the end of the world. Both places I call home, now turned into inhospitable wastelands. In a world where our grief and loss are constantly being outpaced by the frenzy of the world, we are running out of time to mourn everything we’ve lost in the fire. Since when did human relationships become so disposable, so secondary to our existence? In Titanic Rising, all of this culminates on the devastating “Picture Me Better,” where Mering dedicates the song to her friend that she lost to suicide. It is unequivocally one of the saddest songs in her discography. Promises that can no longer be fulfilled, futures that don’t include our loved ones, memories that get lost to time. It’s just a part of living in this day and age.

Because of this, I’ve also found myself “waiting for something with meaning / to come through soon.” How successful I’ve been with this pursuit is a bit more debatable. The thing is, when I was younger I always worried about this exact thing. I’m sad to say that a lot of those fears have come true. I don’t have many friends, I’ve been stuck cleaning and doing clerical work for minimum wage for the past 3 years, and I still don’t really know what I want to do with my life because I’m not particularly good at anything. But lately I’ve learned that waiting this long for something to come along has done nothing except make me feel worse about myself. If I truly was running out of time on this Earth, wouldn’t the best way to spend the rest of that time be to cherish what beauty is left in my life?

With Titanic Rising on my mind, I’ve spent the past few months doing just that. I got to travel to Seattle all by myself, live alone and cook my own food for the first time. I even got to see her perform songs off this album three separate times. I have fond memories of all these moments in my life, but sometimes the uncertainty comes back to haunt me when I realize that even those memories are at risk of being lost to time. The Theater at Ace Hotel, the venue for Weyes Blood’s opening shows for her In Holy Flux tour, recently announced that it would be closing down. A core memory that I share with this album is physically being demolished as we speak. The only emotional vestige I have left of this place lies in the words that I’ve left behind two winters ago. I think I got lucky just this one time, but truthfully I can’t guarantee that I can protect the rest of my past.

I think this is what shapes Titanic Rising’s thematic DNA though, this acknowledgment that our humanity falters under the weight of this naturally entropic world. We can choose the path of fatalist acceptance, but Mering keenly recognizes that this will eventually lead us down a violent rabbit hole of self-importance and indifference. Instead, we can actively work towards preserving relationships and experiences that imbue value to our lives. Befriending strangers you rubbed shoulders with at parties, watching movies that make you laugh hard and cry harder, showing up to work late just so you can spend more time with the girl you like. Because it’s an album deeply haunted by the end of the world, Titanic Rising is also equally infatuated with the minutiae of everyday life. When Mering sings about climate change and digitized relationships, it’s not just because they’re symptoms of a larger societal plague; it’s also because their sources are rooted in human nature, something that’s lost its luster as we’ve grown angrier and bitter towards the world. I once heard that a world without joy or humor isn’t a compelling world to fight for. Maybe it’s why Mering is so protective of our humanhood, and why we should feel the same way.

Since 2019, a lot has changed in my life. I just turned 21 yesterday, and suddenly there are all these things that I can legally do now. I have a whole bunch of new, potentially life-altering experiences waiting ahead of me, but no matter which chapter of my life I’m in, the promises of Titanic Rising have yet to feel outdated and probably won’t for a while. In her own words, “If I wrote a song that was that ubiquitous and was proliferated all over the world and in movies and everything, I would feel that I had completed my mission on the planet… like you complete a mission as a musician when you can finally kind of distill the essence of suffering into something gorgeous.” I think she must be proud knowing that she accomplished that mission.