Being able to draw was once a dream of mine. Corners of my childhood bedroom are still lined with discarded sketches of characters that unintentionally look like knock-off piñatas. I would spend hours online watching “how to draw Olaf” or “make flowers look real,” but quickly lost interest as soon as the petals fell or head rolled lopsided. It was so frustrating because I didn’t understand what I was doing wrong.

This dream dragged behind me like a maltreated stuffed animal, forced to follow me wherever I went. In my junior year of high school, a friend, and very talented artist, saw the tufts of doodles left on the margins of my homework. She offered me an idea: “just look at everything compared to the size of where you start, not the size you think things should be.”

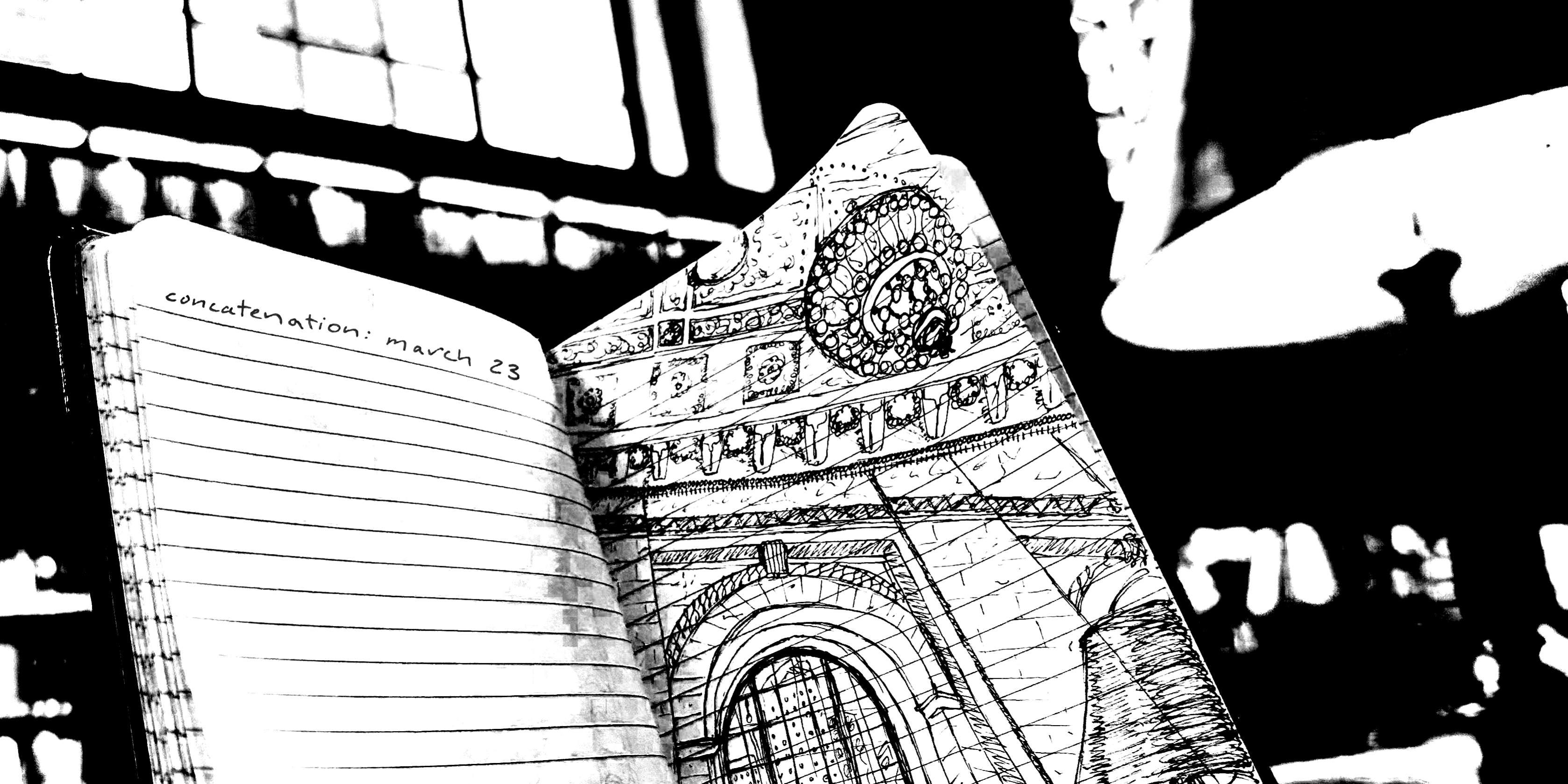

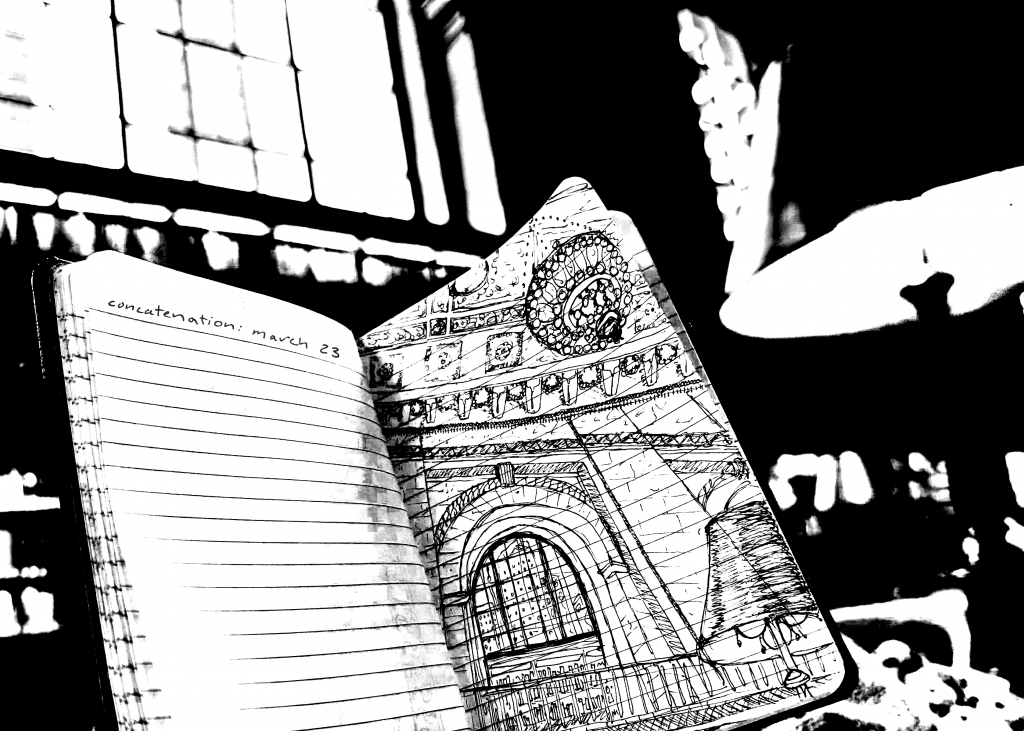

Suddenly I could draw. All it took was that one statement to reframe the world, and the once unimaginable task of forcing perspectives on a page became doable. I was obsessed, and I sketched everything. I found a new way of concretizing my life. And it could be measured as four chairs wide and five chairs tall, as long as the chair was half the size of the lamp in the foreground.

I would mostly draw scenes around me: my drive home from school, my homework sitting on my bed, the buildings I would pass in the city. Part of my obsession with learning to draw was the idea of being able to stop a moment of time as it was, and leave it like that forever. It’s a feeling that undercurrents most everything in my life, the same reason I’m writing these articles, and why I do film. But with drawing specifically, it forced me to stop and really look at how things exist from one view, rather than how they exist on their own. Moments that would otherwise not matter now lasted in permanence, even if it’s just on the backside of a study sheet.

I’m not sure when I stopped drawing. It was somewhere in between half-heartedly graduating high school in a global pandemic and learning to live entirely within a computer screen. Over the last three years, the tangible things in my life migrated from pages to pixels. The sketches got cropped.

Drawing is one of the dreams I pushed aside to make room for other things. It’s not something that I feel particularly guilty for, because I lost interest. I redirected my preservation efforts to other things, photography, film, writing, things that adapted faster to the digital world I was forced to exist in. Consequently, I can feel myself looking at space differently than I used to, no longer eyeing a room to see how many tables deep it goes. Even if things are the way I need them to be, it’s strange to look at what parts of myself I have shelved. And blowing the dust off of my drawing skills doesn’t change the fact that they have been faded by years of sun.

So I am sitting in the New York Public Library, trying to piece together what happened this month. I have little music to share, or coherent thoughts of note, but I thought I’d pick up drawing again just to see what would happen. Honestly, it was harder than I thought it would be, and it took a lot longer than I remember it taking before. But regardless, this moment is sealed forever.

Marginalia is a plural noun that refers to notes or other marks written in the margins of a text, and to nonessential matters or items.

What freak made a playlist like this?